P*DA x TODAY AT APPLE: Lekker Architects on letting everybody play President*s Design Award and Today at Apple collaborate to bring you a series of complimentary workshops throughout the year. Conducted by P*DA recipients, these workshops will focus on different areas in design. This instalment features Lekker Architects. Here’s a low-down on their session at Apple Orchard Road on 1 June 2019.

On a sunny Saturday afternoon, as most kids found their joy in the park or at the beach, a group of children sat restlessly in Apple Orchard Road. Some whiled away their time on their smartphones or partook in hijinks with their peers. Imagination wasn’t in short supply; a little girl turned a leather pouf into a makeshift horse.

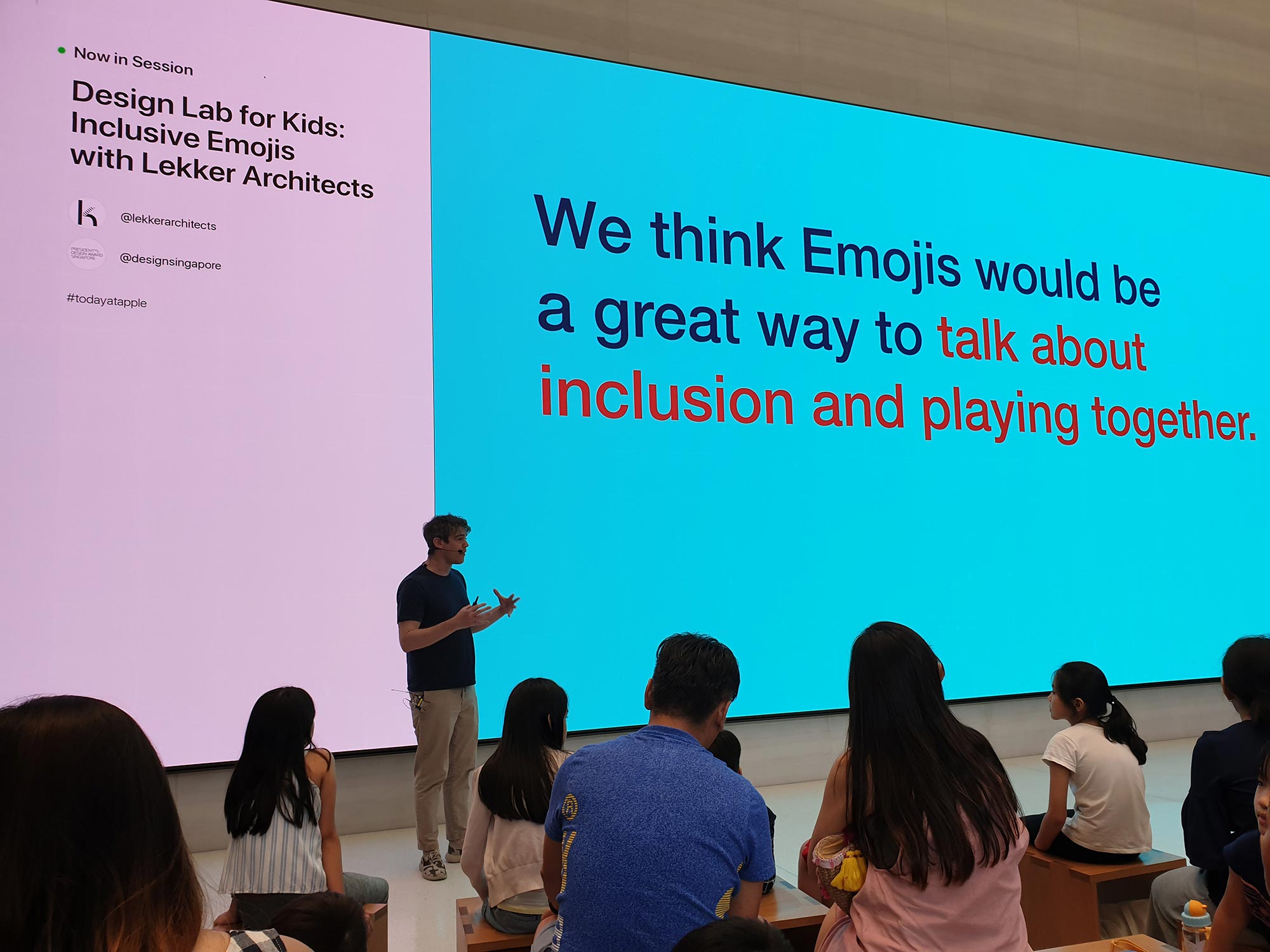

While it might look like bedlam, in truth, they were waiting for a design workshop with Today at Apple to begin: one that would teach them how to create “inclusive emojis” with the husband-and-wife team from Lekker Architects, Josh Comaroff and Ong Ker-Shing.

Josh and Ker-Shing are uniquely suited to lead a workshop on inclusivity for kids – Lekker Architects is passionate about designing inspiring spaces for children of all backgrounds and abilities. Their work is underpinned by the belief that an inspiring space can bolster a child’s creative play, which nurtures the child’s emotional health – a crucial aspect of development.

These principles can be seen in a pioneering preschool project with NTUC First Campus: the Caterpillar’s Cove Child Development and Study Centre@Jurong East, the first of a new generation of design-led local preschools. The school breaks new grounds with an open-concept layout—classes have no walls, with only low curving shelves acting as dividers. The space is divided into different micro-environments to encourage imaginative play. There is also a quiet reading niche as well as an observation area for trainee teachers and researchers to watch the activities without disturbing the children. For breaking new ground in preschool design, Lekker was awarded the President*s Design Award Design of the Year in 2015.

Through their work in designing spaces for children, Josh and Ker-Shing have become more aware about the role of communication in fostering inclusivity. Not all kids are able to articulate their feelings. Even if they can, their words may be misunderstood by adults or other children. Josh and Ker-Shing therefore hit upon the idea of using emojis to help children express their feelings and understand those of others’. After all, everyone, even kids, are familiar with emojis (when asked about a favourite emoji, someone uttered, “the poop emoji”). Emojis are a shorthand whose meaning is immediately clear to the other party.

Josh said, “When you send someone a message, it’s not clear about what they are trying to say. Are you serious? Are you trying to be funny? An emoji tells us what we are thinking, what we are feeling.”

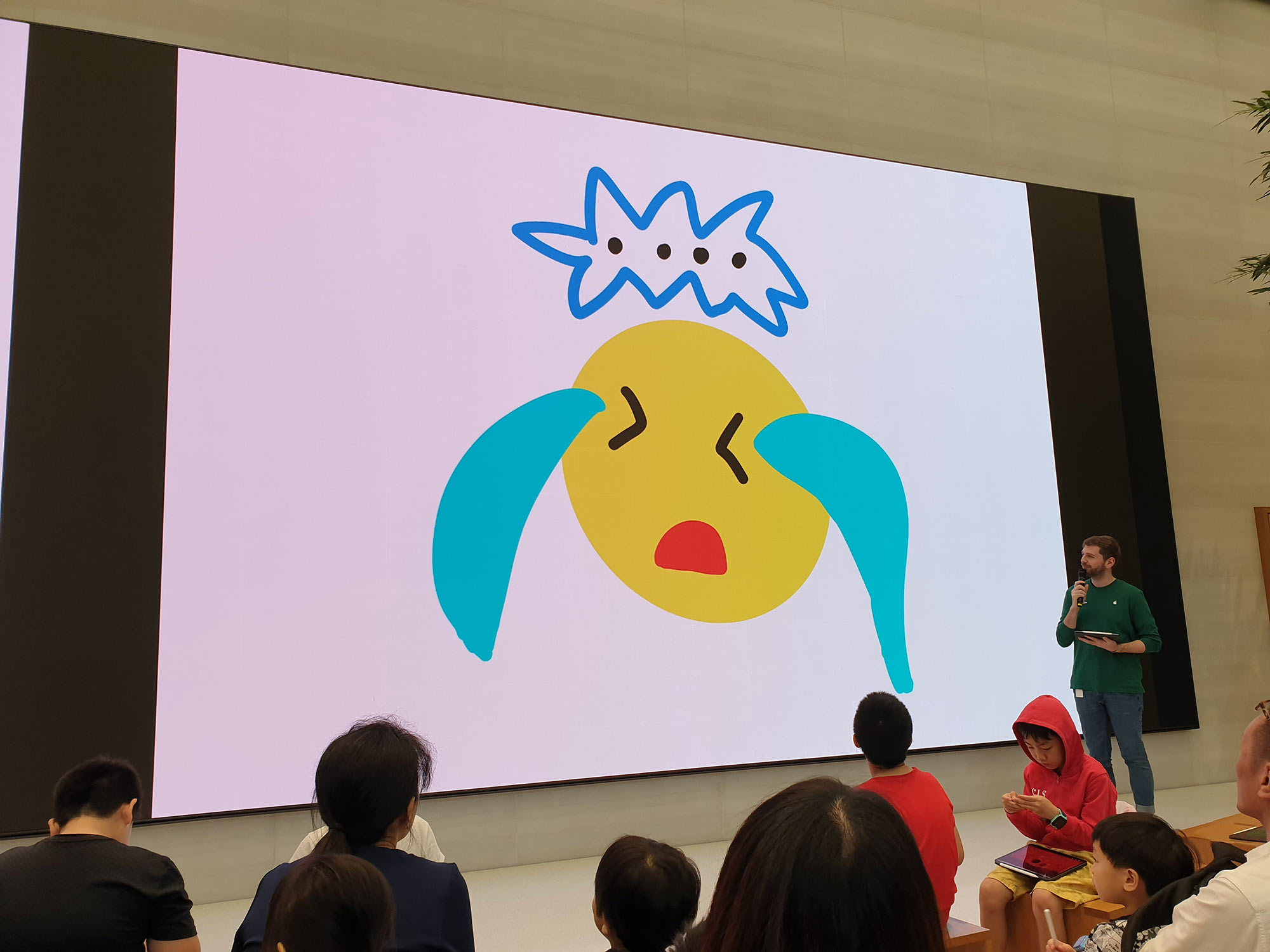

He continued with an example of an emoji where a worried-looking cartoon face warily eyes a set of steps. “Is this guy happy?” he asked, “No, right? He’s a little bit scared and he wants to go [to the top of the steps] but he can’t. That’s a shame. He’s being left out.” In this session, he explained that everyone would learn to create expressive “inclusive emojis”.

iPads were then handed out to the kids, and Josh instructed them on how to make basic shapes for their emojis on the Procreate app. Then, Ker-Shing set up a list of five situations, asking the kids how they would feel when confronted with those circumstances. She invited them to create emojis based on those feelings.

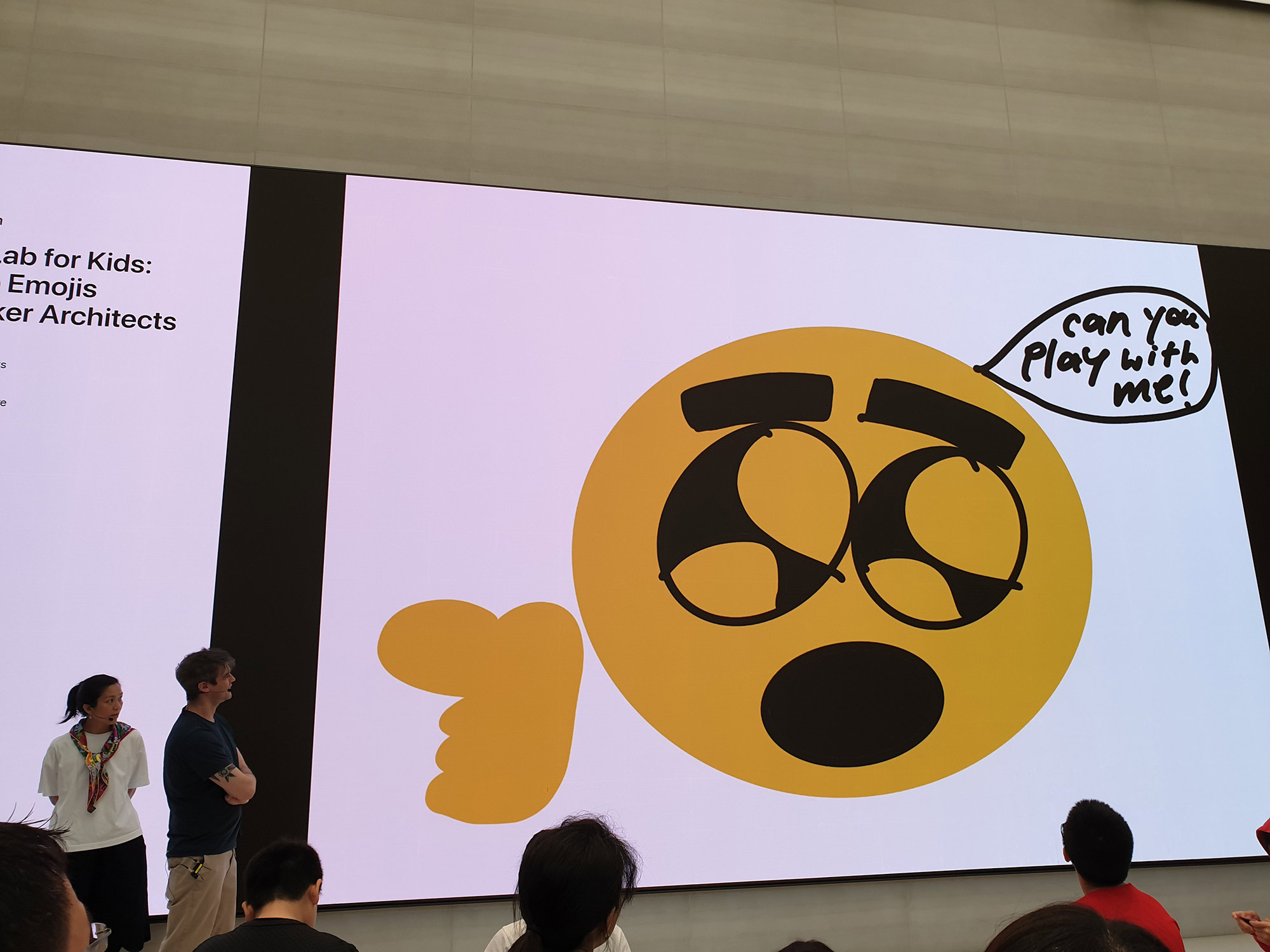

“My younger brother, or sister, or friend, won’t let me play,” Ker-Shing said. “How does that make you feel? How will you create an emoji that describes that? There are no right or wrong answers.”

The other four examples were, “I can’t do that”; “This place makes me happy”; “Would you like to play with me?”; “Can you lend a hand?” The kids could pick an example to create an emoji on or do all five.

The kids were also taught about the use of lines and colours to express different emotions. The end results ranged from the minimalist to the detailed. Some kids were prolific and handed in multiple designs. Towards the end of the workshop, participants were encouraged to talk about their emojis.

To conclude the session, Josh informed the parents who were interested in learning more about the session to check out Vivian Gussin Paley’s You Can’t Say You Can’t Play, which talked about inclusive design. He also recommended Superhero Me, an inclusive arts movement. The children took away what it felt to be excluded from activities. By channeling their emotions in emojis, they would be better equipped to understand and empathise with those of different abilities.

+++

Q&A with Lekker Architects’ Josh Comaroff and Ong Ker-Shing

How did you think the workshop went?

Josh: The kids seem to be super engaged and they had great ideas. I was worried that everyone would draw the same emoji and it turned out not to be the case.

Ker-Shing: It’s quite incredible. Children pick up things so quickly that even at today’s workshop, you’d think that you needed time to explain to them on how to use the app and the iPad but they just jumped straight in. I think that’s a fantastic way to learn: kids trying things out and not have to be told step-by-step on how to do something.

Was there anything you wish could be improved?

Ker-Shing: Well, it’s quite tough when you have an audience between the ages of six to 12. Today’s session had kids who were on the younger end of the spectrum and it’s difficult to be complex when describing that emojis had to explain something very specific and also very complicated.

Josh: One of the things that’s always a challenge is getting the kids to talk about their work. Because it’s a big venue and they are surrounded by other people, they feel a bit discouraged to talk. There must be some tricks in getting them to open up. We’ll need to figure that part out.

Some might be curious as to why architects are dealing with emojis.

Josh: Everyone experiences architecture but weirdly, it’s kind of tough to talk about, I think. In the sense of understanding how buildings work and what they are trying to express, architects have never been super great in explaining their work to the general public.

For us, it’s interesting and helpful to talk about things through other ways. In this case, emojis have an immediate way of clarifying language that sometimes can be a little too vague.

It sounds like inclusivity is near and dear to your heart.

Josh: I think, for many people, the sense of being excluded is one of the worst things that they can feel. Scientific studies on the actual effects of children being excluded and the emotions that they feel are on par with verbal or physical abuse.

Ker-Shing: It’s a form of trauma.

Josh: Yes. People tend to carry that trauma into the later part of their lives. When we think about places and spaces, their accessibility and openness are really important to us.

What do you think about inclusivity in Singapore’s built environment?

Ker-Shing: We talk about the legislation and the provisions to ensure that a structure is accessible—there’re ramp access and stairs. Whether you’re in a wheelchair or not, everyone should be able to enter a building. The sizes of signs, being able to navigate… those are easily provisioned for in code.

We’ve done projects on inclusive schools but another big project that we’re doing now that’s nearing completion is a neighbourhood-wide study on whether people feel comfortable in their district as they get older.

It’s a qualitative study and we realise that the soft aspects are hard to provision and code. Yes, you have a ramp and stairs but is that ramp intimidating?

Josh: Or is it really far away.

Ker-Shing: Or is there any shelter… all these are the soft aspects, the feelings and interpretation. That is something that we’re missing.

So how can this be improved?

Ker-Shing: When more projects take in designers, the quality will go up. For example, before we won the President*s Design Award for the Caterpillar’s Cove, the level of design for childcare was very low. Nobody thought of hiring design architects for childcare centres.

But after winning that award, people realised that children need good design that can strengthen the curriculum.

Josh: There are two things there: one is that clients are reaching out to designers and the second is that designers discover that this is an interesting space to be working in.

Shing teaches at NUS (National University of Singapore) and I have been teaching at SUTD (Singapore University of Technology and Design) for the past few years. We get many students choosing inclusivity and broader social inclusion issues as their thesis topics. It seems that there are a lot of younger designers who are interested in the subject. Based on that, I guess there will be interesting new ideas coming from that generation.

What’s next for Lekker Architects?

Ker-Shing: We’re designing a hospice day-care centre right now. Obviously everybody there has been diagnosed with a terminal illness and there is this concern on how you design a space for people to spend their last days. This is another way of thinking about inclusive design that is not only for everybody but also elevates the quality of life for the aged. It’s not so much about whiling away one’s time but how do you give back that quality of life.

Josh: We’re also working with IKEA on hacks for dementia. The great thing about IKEA is its global accessibility. We’re working with the Lien Foundation to make it easier for the carers of dementia patients by “hacking” IKEA furniture to make them more dementia-friendly.

+++

Article written by Wong Chee Yan. Watch this space for the next P*DA x Today at Apple workshop, scheduled once a month until December 2018. Upcoming workshops will be updated here.