* DESIGNER OF

THE YEAR 2011

Mr Chan went to boarding school in England when he was 15. His interest in architecture as a profession was influenced by his two cousins who were studying the course. “Their design started from a blank sheet of paper, which I found emotively stirring,” he explains. “And at the same time, it meant I could leave boarding school two years ahead by enrolling in the Northern Polytechnic in London.”

Upon graduation in 1963, he applied to the Architectural Association School of Architecture for the course in Tropical Studies. He said: “As with my generation, we were caught up with the fervour of gaining independence from the British colonial government and the desire to return home to practise, so the course was relevant as its emphasis was on designing for the climate in the tropical belt.”

Since his return from London to join Kumpulan Akitek in 1964, Mr Chan’s concern for climate, culture and appropriate technology is a defining feature of his portfolio of works in Southeast Asia, India, China and as far as Morocco.

Hyatt Kuantan, completed in the 1970s, was his first opportunity to apply the knowledge acquired from his graduate studies. Being a beach resort, it was an ideal building type to demonstrate design in the tropics with optimal natural cross ventilation, sun shading and rain protection provided by pitched roofs with generous overhangs and open sided verandahs. This was typical of the stilted Malay kampong house, and re-interpreted the colonial black and white house. “It was a distinctively fresh approach of looking inwards at our heritage for inspiration instead of the West,” says Mr Chan.

Hyatt Kuantan spawned a building typology which became a populist imagery for subsequent building by others. Till today, Mr Chan feels that Hyatt Kuantan Hotel has been the point of departure of his current architectural development.

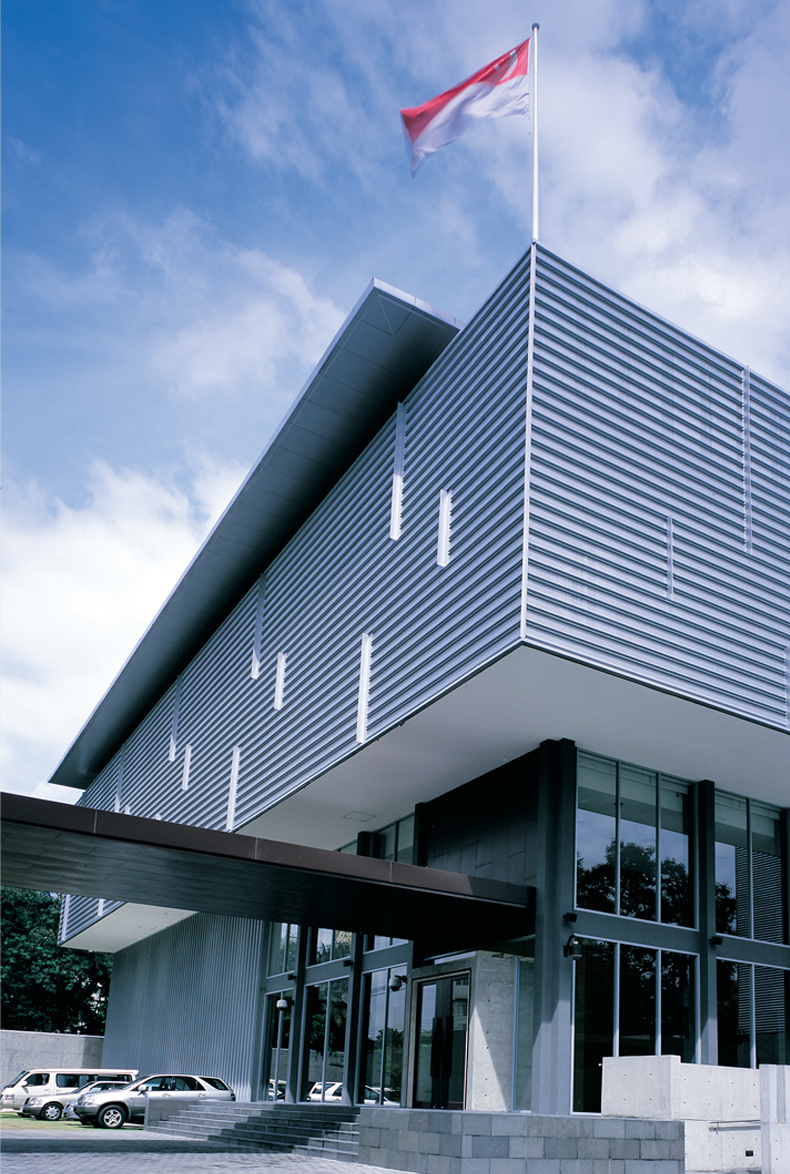

In 1993, he left his previous partnership and found his present practice under Chan Sau Yan Associates (CSYA). He began experimenting with designing tropical highrise when he submitted a competition entry for the design of Maybank headquarters in Singapore in 1998. Though unsuccessful, it served to inform the design for his Tokio Marine Centre in 2007.

One distinctive feature of the Tokio Marine Centre, the award-winning design, is its “exoskeleton” façade of seemingly random columns. Mr Chan says that the bamboo grove is the design metaphor for the building which his client found appealing. The criss-crossing of the columns is not an aesthetic consideration, but has a structural and functional purpose to stiffen the building and provide sun shading, unlike the typical office building with a curtain wall of glass.

While he adapts his designs for the climate, culture and technology, Mr Chan believes that architecture should be honest, staying true to his educational modernist roots. “What we try to see through is the complexity of the problem and seek a simple solution. We like to express materials in their natural state,” he says.

For example, the concrete of Hyatt Kuantan Hotel and Tokio Marine Centre were left fairface even though these building types are conventionally cladded over. Another project, The Bishopsgate house, is entirely in fairface concrete, including the roofs. “If you’re building with concrete, it’s already water-tight, why do you need to finish it off with something that is just cosmetic?” he asks. “We think it is so unnecessary”.

Such radical views are not easily accepted by clients, but Mr Chan says spending time and effort to convince them is partand- parcel of architectural practice. “Virtually all architects face the challenge of convincing clients to go beyond the typical approach,” he says. “The only question is whether you are prepared to persevere and convince them.”

And while some attribute the same spirit of perseverance to his almost five decades career as an architect, the 70-year old is surprised at how long he has been at it. “It doesn’t seem so long because I’m enjoying it. We’ve been fortunate to get one client after another, each with a different project, so I’ve never thought of retiring,” he says.

READ MOREInsights from the Recipient

Jury Citation

Sonny Chan pursues authenticity with a deep passion. Guided by his three key precepts — sensitive response to climatic conditions, harnessing of appropriate technology and a deep understanding of local culture — Sonny’s designs achieve a high level of sensitivity, originality and intelligence which have become hallmarks of his works. This remarkable body of work, which has emerged over a long career, is characterised by rigour, seriousness and rich architectural expression.

Sonny’s technical knowledge is exemplary. His passion for tropical architecture translates into designs that demonstrate strong contextual and cultural relevance. His acute sensibilities towards local vernacular architecture, such as natural ventilation and minimal mechanical intervention, were adopted early in his career, and through his diligent application and skills, tropical architecture has been brought into a modern idiom.

Sonny continues his successful practice after almost 50 years, and remains committed to practising architecture and is an excellent role model and inspiring mentor to the local and wider architectural community of the region.

VIEW JURORSNominator Citation

KERRY HILL

DIRECTOR

KERRY HILL ARCHITECTS PTE LTD

Sonny has been both a friend and colleague for more than thirty years, during which time I have watched his quiet but sustained pursuit of an appropriate and contemporary tropical regional architecture. He has immersed himself in the discourse about designing for the tropics since postgraduate studies at the Architectural Association School of Architecture in the early 1960s, and remains true to this interest until today.

Over the years, his work has progressed from literal representations to more abstract building solutions. This is a result of his experiments to test new possibilities for building in the tropics. His early mediumdensity housing designs displayed innovation that we now accept as common place. His embassy building projects in Bangkok and Phnom Penh represent Singapore well, being both contemporary and appropriate to the context of their respective host countries. His 1998 Maybank competition entry remains an important, conscious, and intelligent attempt to design a tropical high-rise.

It is Sonny’s single residential designs, however, that best embody and chart both his personal architectural aspirations and his ultimate contribution to the tropical discourse. His house plans have always responded to place and passive climate control. More recently, these plans have displayed a clarity of diagram that can only evolve through a mature understanding of the building type.

Sonny is a collaborator and mentor who has remained utterly committed to architecture for a working life of almost fifty years. To my knowledge, he intends to continue. This unwavering commitment to the discipline, and the willingness to share his now considerable knowledge, makes Sonny an invaluable contributor and resource within the wider architectural community of the region.

I take great pleasure in nominating Sonny for the President’s Design Award as a befitting tribute to an architect of integrity, and quiet but immense sincerity.