DESIGN OF THE YEAR 2023

Hack Care: Tips and Tricks for a Dementia-friendly Home

Designer

Lekker Architects

In collaboration with Lanzavecchia + Wai

CONTACT

[email protected]

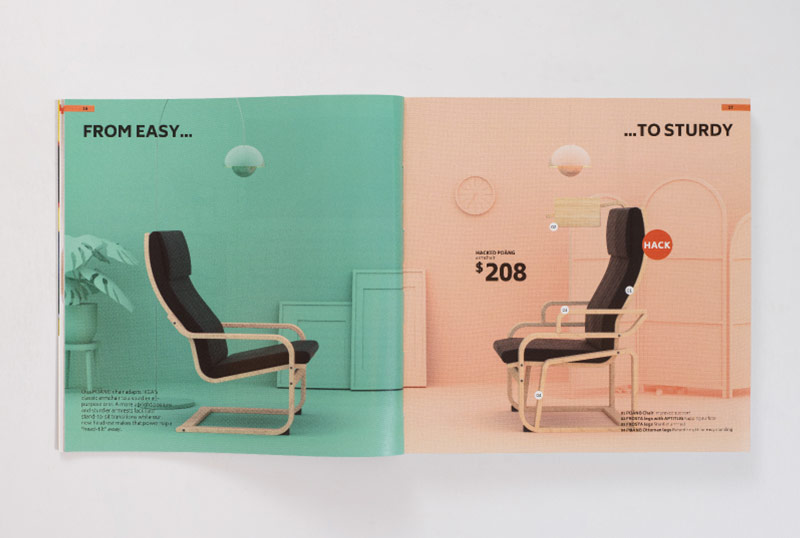

The blissful families in welcoming domestic settings look right out of a furniture and homeware catalogue. But this is no sales pitch. Instead, Hack Care is a manifesto outlining how anyone can easily turn their home into one that is friendly to persons with dementia.

The 244-page guide by Lekker Architects in collaboration with Lanzavecchia + Wai offers practical tips and tricks for hacking existing furniture and products into solutions that support caring for people with dementia. Adapted with accessories, an armchair transforms into a care station. Switches, locks, and textiles assembled onto a chopping board create an object for the therapeutic activity of fidgeting. Even the considered arrangement of furniture and familiar objects helps, as the guide explains. The many hacks are presented in an easy-to-understand manner for anyone to access and are highly affordable too.

Going beyond a toolkit, Hack Care redefines what design is and who can practice it. Instead of offering fixed solutions, design becomes a process of making and experimenting. It is not just the domain of professionals but also part of everyday human activities. Just as the guide supports caregivers in the creation of a more inclusive home, it opens up access to the world of design.

About the Designer

Lekker Architects is a multidisciplinary practice that explores the social-emotional potentials of design. Co-founders Ar. Ong Ker-Shing and Dr Joshua Comaroff studied environmental design (architecture and landscape) and social science (cultural geography). They combine methods from both areas to search for designs that help people to learn and grow, and form more inclusive kinds of collective relationships.

They are excited by the challenge of catering to the full variety of human bodies, minds, and experiences – not just because it makes lives better, but also because it makes for more compelling design.

Alongside her role as Director of Lekker Architects, Ong is Associate Professor (Practice) and Bachelor of Architecture Programme Director at the National University of Singapore’s Department of Architecture. Comaroff is an Assistant Professor in Urban Studies at Yale-NUS College. His PhD studied haunted landscapes and urban memory in Singapore.

Lekker Architects received a P*DA Design of the Year in 2015 for The Caterpillar’s Cove preschool, the 2020 Singapore Institute of Architects’ Design of the Year for the Quiet Room in the National Museum of Singapore, and the Urban Redevelopment Authority’s Architectural Heritage Award in 2013 for a home and gallery in the Lorong 24A Shophouse Series. Ong and Comaroff are recipients of the Wheelwright Traveling Fellowship from the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

Lanzavecchia + Wai, established in 2010, is an internationally renowned award-winning design studio based in Italy and Singapore. The studio’s work includes research projects for Herman Miller, limited-edition objects, and mass products for brands such as Zanotta, FIAM, Living Divani, LaCividina, Cappellini, De Castelli, Gallotti&Radice, Bosa, Nodus, and Mirage. Lanzavecchia + Wai’s work also includes special commissions for major brands and museums such as Hermès, La Triennale di Milano, Wallpaper*, MAXXI, M+ Hong Kong, Antolini, Tod’s, AgustaWestland, and Alcantara.

The studio’s many accomplishments include being awarded the “Young Design Talent of the Year” by Elle Décor International Design Awards 2014, the Archiproducts Design Award, the Red Dot Award Product Design 2016, and the Innovation in Inclusive Design Practice Award of the Royal College of Art.

DESIGNER

Lekker Architects

PHOTOGRAPHER & VIDEOGRAPHER

KHOOGJ

CLIENT

Lien Foundation

COLLABORATOR

Lanzavecchia + Wai

PRINTER

Oxford Graphic Printers Pte Ltd

DESIGNER

Lekker Architects

PHOTOGRAPHER & VIDEOGRAPHER

KHOOGJ

CLIENT

Lien Foundation

COLLABORATOR

Lanzavecchia + Wai

PRINTER

Oxford Graphic Printers Pte Ltd

1HACKING IS CARING

Inspired by the inventiveness of caregivers and their own personal experience, Lekker Architects initiated this toolkit to share ways of adapting and modifying objects and spaces to create a friendlier environment for people with dementia.

(Photo by KHOOGJ)2FROM A CHAIR

A starting point for the project was hacking a chair for care recipients who have lost their mobility. The designers explored a variety of hacks that could allow this piece of furniture to function as a “second home”, including prototyping ways to make it sturdier so that care recipients can stand more easily.

(Photo by KHOOGJ)3ACCESSIBLE TO ALL

Unlike many existing design guides, which can seem abstract to readers not trained in design, the toolkit is styled like a furniture and product catalogue – enticing and easy to read. It offers practical advice and is accompanied by four do-it-yourself guides on how to hack commonly owned furniture as well as stationery to encourage readers to get started.

(Photo by KHOOGJ)4DESIGN AS ACTION

The toolkit encourages readers to see design as something they can carry out for themselves. While explaining key design principles, it offers interventions that are simple to carry out. For instance, to ensure the bathroom is “visually legible” for people with dementia, one can choose contrasting colours for important items such as grab bars.

(Photo by KHOOGJ)5EVERYDAY CARE

The “Daily Rituals” section of the guide outlines activities that caregivers can organise throughout the day. For example, they can get care recipients involved in the preparation of meals, using widely available kitchen equipment to ensure the experience is safe and enjoyable.

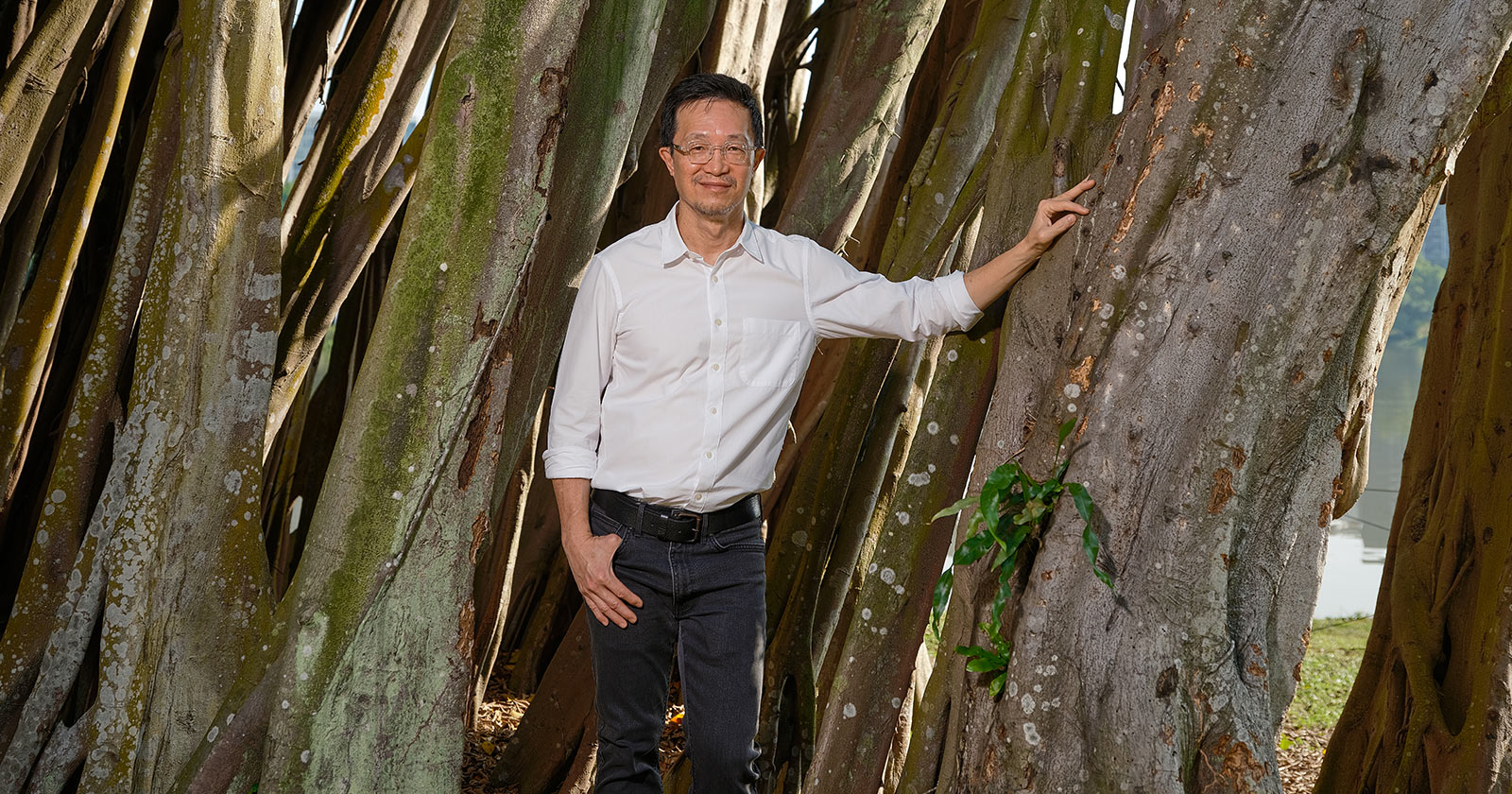

(Photo by KHOOGJ)(L-R) Lee Poh Wah (Lien Foundation); Joshua Comaroff and Ar. Ong Ker-Shing (Lekker Architects); Francesca Lanzavecchia and Hunn Wai (Lanzavecchia + Wai).

(Photo by Ivan Loh)Insights from the Recipient

Ong Ker-Shing (OKS): Before this project, we had already been designing for users who are not the typical clients one imagines when entering practice… After completing A Different Class, a book of ideas pushing the envelope on preschool designs, we began discussing with Lien Foundation what to work on next. Dementia came up as a pressing concern, and it was not just academic, but personal for us as my late father suffered from it…

From the initial discussions, we wanted to look at how to democratise design so people feel they can do it too. Our experience caring for my father taught us that dementia is unfortunately a one-way street at the moment. It is decline. It is inevitable. It is constantly changing. There are no design solutions that are generalised enough to help with all the changes to a person with dementia…

We noticed our family constantly came up with solutions that were motivated by our love for and knowledge of our father. A lot of other caregivers do that too and even share their solutions with others. There is so much of such innovation in care that is under the radar of big ‘D’ design. We wanted to create a book to highlight these solutions and this attitude.

Joshua Comaroff (JC): We noticed a lack of guides outside of the medical space on how to care for dementia patients. There are many great books with high-level design principles for dementia care, such as be patient centric, keep engagement active, make a space that is visually clear… but how do you actually do that? … [B]etween the design principles and actual experience, caregivers were already coming up with their own solutions by hacking.

Our idea was to marry the design principles with this treasure trove of inventiveness that has come out of necessity from all these caregivers who are underequipped and underpaid in every capacity. We wanted to create a primer to help people who are going through this process of caring for someone with dementia.

JC: The sense was we needed something that was very general and accessible. If dementia designs and principles are arcane and expensive, how do we present them in a way that is affordable and available to more people? What is a byword of accessibly in design? That was when we arrived at the idea of the IKEA furniture catalogue. We mocked up a sample for a meeting with Lien Foundation’s CEO Lee Poh Wah. Before we could show it to him, he said: “We need something like an IKEA catalogue.” That was the moment when it was, “Boom!” It was incontrovertible alignment.

OKS: We also always turned to IKEA for our solutions. My father suffered from frontotemporal dementia and one of the symptoms was that he started losing connection to a sign and what it signifies. He didn’t know a knife was for cutting. He started associating water with his IKEA tumbler and only drank from it. These tumblers are cheap and accessible and so my aunts and uncles got them for their houses so my father could drink water when we visited with him.

The IKEA furniture catalogue is also highly recognisable. Everybody likes thumbing through the catalogue, and it was very important that our guide was not seen as elite or disempowering so that people would pick it up too.

JC: There were two aspects of testing. One was learning from the experience of the caregivers, which was really important. A lot of the hacks were things that people had already tried. For example, we learnt from Shing’s mother to have two twin beds next to each other – one wrapped with a shower curtain – to manage a person with dementia wetting the bed. This way, you can just switch the person to another bed when it happens and handle the mess later.

Another form of testing was letting other caregivers try our hacks. The cool thing about hacking is that you are tweaking and not designing entirely from scratch. It was a very lively process of adjusting things for different conditions, bodies, and preferences. This was really the ethos of the project. It was a way of going against the notion of design as delivering final products, but rather thinking of it as a process of ongoing engagement with the physical world and objects.

JC: The “Daily Rituals” theme addresses the temporal sequence of care. Someone once said that warfare is long stretches of boredom punctuated with short periods of terror. Care is very much like that. So, the hacks offer a structure of activities that becomes really important. The “Microworlds” section is about hacking the spatial relations of the objects with the environment, which is very important too. You could design a wonderfully efficient care station, but it could be marginalised if it is just isolated in the corner of the room.

OKS: We really believe that environment matters. It affects the way you feel and perform, and this guide makes that argument. Josh mentioned earlier that my father was incredibly sensitive to the environment. Everybody is. It becomes apparent when you are focusing on how they respond to certain things. The fact that the hacks in the guide can be done by anybody shows how you can improve your environment in many small ways. In this way, I think the guide reaches beyond the subject of dementia care, too.

JC: On the one hand, we don’t believe that everybody is a designer. Design is really hard. The more you engage with design as research, the more you understand the complexity you are designing for. But we also want to acknowledge the adjacency of design intelligence to a natural human ingenuity. There are certain things that people who have not gone to design school do that are very, very close to how designers solve problems. With this guide, we acknowledge that there are these forms of design and creativity happening organically. As designers, we can draw them out, talk about why they work, and situate them. It is really design at its best: mediating spheres that don’t normally talk to each other…

OKS: I don’t think it’s about making everyone into a designer, but about rethinking the designer as a provider and the people who use design as just recipients. This guide is not about providing a set of instructions to carry out to have a perfect outcome. It’s about a thought process and empowering people with a mentality of hacking. With projects of this type, what’s really important is getting conversations going. Who would have thought we could talk about dementia and its unglamorous effects, like wetting a bed, in the context of the P*DA? What’s really important is that it becomes okay to talk about these things, because frankly all of us know somebody who is going through dementia.

Citation

Jury Citation

Nominator Citation

Lee Poh Wah

Chief Executive Officer

Lien Foundation

Hack Care is a timely, important, and highly accessible piece of work that raises public awareness around providing a life of dignity and grace for persons with dementia. Put together with sensitivity and beautifully designed, the book and toolkit offer creative, affordable, and practical ideas for improving the home environment with simple design hacks and innovations. It encourages and empowers caregivers, as well as seeds advocates for inclusive design with every hack.

The Jury commends the project for its powerful message of normalising dementia – positioning it not as a strictly defeating problem but as a prompt to act, adapt, and create a better experience of daily life through ‘hacking’. The Jury also recognises the designers’ attitude of facilitation, rather than prescription, through design – they refer to family caregivers as designers in the project, along with their intention to open a much-needed deeper debate as to how a complex societal issue such as dementia may be tackled.

Hack Care provides a valuable reminder that now more than ever, it is critical to challenge our preconceptions and shape behaviour and thought around dementia, with one in 10 people above the age of 60 years living with the condition in Singapore.

Two years after the completion of Hack Care, the Lien Foundation can, in our capacity as client, confidently attest to the project attaining outcome-based success.

In work of such a nature, measuring design’s impact is difficult. But the impact of Hack Care can be clearly gleaned from the public’s demand for it. After the original print run of 2,000 copies, which we believed would satisfy the community’s appetite, we had to make a second print run of 1,500. The demand came from exactly the stakeholders who mattered: end users and subject matter experts.

A quarter of the copies were requested by the former (caregivers of persons with dementia), while half were requests from the latter (professional staff from the medical and social services). Caregivers took design into their own hands, putting Hack Care into practice through their experiments with household items to elevate the quality of their loved ones’ lives. Professionals did likewise in eldercare centres and nursing homes, improving lives at a larger scale.

Impact was felt in the design fraternity too, not only locally but also internationally. The project was covered in reputable overseas media such as Wallpaper*, Design Wanted, Elle Décor, and Dezeen. The book inspired designers around the world to look at dementia, an illness that affects millions, through the usually staid vantage point of the domestic.

The project’s success could not have been presumed. The design challenge was complex, and Lekker Architects worked amid painful personal challenges. But the studio dug deep and – on its own initiative – spent three years working on Hack Care alongside its cross-discipline collaborators at industrial design studio Lanzavecchia + Wai, as the vision grew.

This is a special story of designers who reframed adversity as inspiration, using design, satire, and common sense to make a point.

Disclaimer

The ideas in the Hack Care catalogue have been gathered to suggest ways to improvise and expand care for persons with dementia. While every effort has been made to ensure that the hacks contained in the catalogue do not pose any undue health and safety hazards, the Lien Foundation nonetheless urges all readers to exercise their own judgement on the safety, suitability and appropriateness of these ideas to their own respective caregiving situations. Readers are encouraged to do their own research, and to always consult a professional when in doubt.

Hack Care is a social initiative led by the Lien Foundation and is not related to IKEA®, the Inter IKEA Group, or the Ikano Group. All references to IKEA® products are presented for the reader’s convenience only and do not imply IKEA®’s approval of the modification of their products. IKEA®, the Inter IKEA Group, the Ikano Group, and the team behind Hack Care shall not be liable for any product failure, damage or personal injury resulting from the use of the hacks featured in the catalogue.