DESIGNER OF THE YEAR 2020

Kelley Cheng

Creative Director

The Press Room

CONTACT

[email protected]

Start a magazine. Publish books. Run a gallery-cum-bar. Teach graphic design. Inspire her generation and others after. Kelley Cheng has done them all. It is no wonder she introduces herself not as a designer but a “modern-day polymath”.

It all started when Kelley left behind her architecture training to pursue her love of magazines. In 1999, the 20-something started iSh, a pioneering magazine that provided a platform for Singapore’s emerging creative scene and introduced design to

the masses. It was bought over two years later by local bookstore Page One, which also appointed Kelley to start its publishing arm. Over the next eight years, she oversaw the creation of over 1,000 art, design and architecture books while keeping iSh going.

In 2009, Kelley started a new chapter when she launched her studio, The Press Room. By then, she also co-founded Night & Day and 15 minutes, two much-needed alternative

spaces for Singapore’s burgeoning creative community. Her desire to nurture the next generation of creatives has only grown over the decade as she mentors her employees and lectures part-time.

A storied career spanning over two decades has not stopped Kelley from looking out for the next adventure. “This is the true spirit of any creative”, she says.

1KELLEY CHENG

(Photo by Ivan Loh, pigscanfly photography)2A DESIGN CHAMPION

Kelley started the magazine iSh in 1999 to showcase Singapore architecture and design. It ran for a decade with her as the Editor-in-Chief and Creative Director.

(Photo by Kelley Cheng)3ARCHIVING ARCHITECTURE

Through her magazine and

publication work, Kelley has helped to document Singapore architecture and

design culture. As the Editor and Creative Director of Singapore Architect, she interviewed many pioneering local architects. In 2015, she designed Our Modern Past, a comprehensive visual survey of Singapore’s modern architecture heritage by Ho Weng Hin, Dinesh Naidu, Tan Kar Lin and Jeremy San.

4ARCHIVING ARCHITECTURE

Through her magazine and

publication work, Kelley has helped to document Singapore architecture and

design culture. As the Editor and Creative Director of Singapore Architect, she interviewed many pioneering local architects. In 2015, she designed Our Modern

Past, a comprehensive visual survey of Singapore’s modern architecture heritage

by Ho Weng Hin, Dinesh Naidu, Tan Kar Lin and Jeremy San.

5CREATIVE SPACES

Night & Day was a space set up by Kelley and some friends in 2007 for creatives in Singapore to showcase their works and to network. The edgy bar located in a shophouse along Selegie Road was known for its eclectic and free-spirited setting.

(Photo by Kelley Cheng)6CREATIVE SPACES

Night & Day was a space set up by Kelley and some friends in 2007 for creatives in Singapore to showcase their works and to network. The edgy bar located in a shophouse along Selegie Road was known for its eclectic and free-spirited setting.

(Photo by Kelley Cheng)7THE ARCHITECTS’ DESIGNER

Although Kelley gave up practising architecture, she has designed for many in the industry such as Singapore’s pioneer architect, Ar. William Lim. He co-founded the Asian Urban Lab and Kelley designed several books published by this non-profit to facilitate multidisciplinary research on life in Asian cities.

(Photo by Studio W)8PROPORTION & EMOTION

To celebrate Kelley’s 20 years in design in 2019, DesignSingapore Council co-presented a retrospective exhibition of her work at the National Design Centre. She curated and designed the show – summing up her design approach as a balance between proportion (form) and emotion (content).

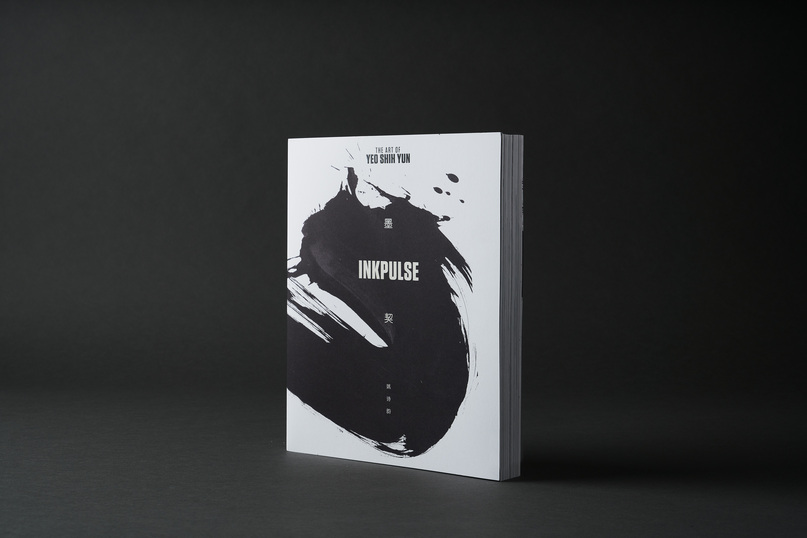

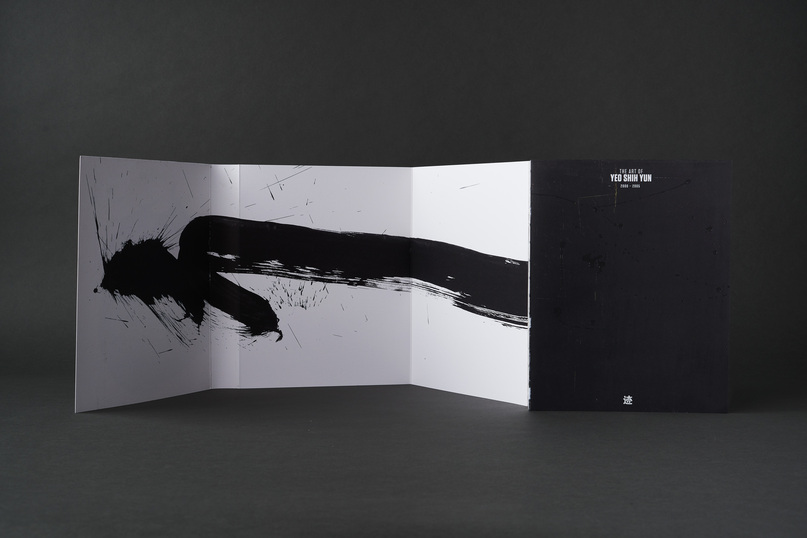

(Photo by Kelley Cheng)9THE ART OF DESIGN

Having had no formal training in graphic design, Kelley found her own design approach. As seen in this monograph for artist Yeo Shih Yun, the designer treats pages as canvasses where she freely places elements rather than rely solely on formulaic grids.

(Photo by Studio W)10THE ART OF DESIGN

Having had no formal training in graphic design, Kelley found her own design approach. As seen in this monograph for artist Yeo Shih Yun, the designer treats pages as canvasses where she freely places elements rather than rely solely on formulaic grids.

(Photo by Studio W)Insights from the Recipient

Kelley Cheng (KC): I loved drawing since I was young. In secondary school, I visited bookshops to browse magazines like The Face, Dazed & Confused, Ray Gun, Bikini… I didn’t know what design was, but their edgy layouts and visuals were very attractive. I became very interested in taking photographs and even became the chairperson of my school’s photography club. My dream was to go overseas to study photography, but my parents asked me to study in Singapore due to our financial situation. In the early nineties, there wasn’t a degree in photography or design offered here, so I ended up studying architecture at the National University of Singapore. That was where I was first introduced to the Apple Macintosh. I played around with it a lot and even created my first fanzine. It was a compilation of my random thoughts about architecture and interviews with my schoolmates about life in architecture school. I photocopied the zine and forced my friends to buy them at S$1 a copy!

While still in school, I also cold called magazines to freelance as a photographer and writer. I just knew that I wanted to work in publishing more than in architecture. My internships at architecture firms confirmed this hunch. A year or

so after graduation, I joined architecture and interior magazine, ID, and worked there for almost two years before it closed.

KC: It was really a rojak (Malay word meaning mixture) of ideas. For the lack of a better term, my vision was a “design lifestyle” magazine. iSh’s tagline was “fragments from

the urbanscape” which allowed me to cover fashion, food, architecture. This would appeal to people other than the handful of designers in Singapore’s small market. I

also believe a lot of things are related to design. One of my inspirations was Wallpaper*, which was a landmark magazine in the nineties that combined fashion,

travel and architecture. It did a really good job bringing design to people, and I thought of iSh as the Asian version of it.

Looking back, I think I tried to do too much, but the magazine was really an experiment. I did the first few issues on my own because I couldn’t afford to hire. But it was very exciting for a 20-something. The magazine became sort of a representation of my design approach. I prefer a non-linear approach in my designs and for things to be all over the place to see a bigger picture.

KC: One of the key reasons I started iSh in 1999 was to give young creatives a platform to develop a portfolio because I knew how difficult it was to get noticed. We featured many Singapore designers of my generation — Kinetic, PHUNK, FARM — because the design scene was small and there was no active organisation like the DesignSingapore Council then to promote them. I wanted to continue supporting young creatives but in a physical space. My partners and I recognised the need for more independent, privately-funded venues for creatives. While the creative ecosystem requires structured government spaces, it also needs alternative ones to nurture unexpected and experimental ideas. At Night & Day and 15 minutes, we got so many requests from musicians who wanted to play for free and artists who wanted to put up exhibitions. I saw myself as a “curator of the uncurated” who provided spaces for anyone who had potential. We gave visual artist Andy Yang and street artist Speak Cryptic one of their earliest shows in 2007 and 2008 respectively, and they are both very accomplished now.

People did a lot of crazy things that did not have a place anywhere else. We once had an artist display tonnes of sand which left a permanent mark on the floor! These venues lasted for a few years and never made money, but we saw it as our way of contributing to the creative community.

KC: As a recipient of the P*DA, I believe I should be an ambassador and advocate for the design industry. There are many young designers who may face similar problems and find it hard to be heard. I am in the position to initiate some difficult conversations.

I can think of three things that are important in creating a better design community. One is to get rid of “unlimited changes”, which some clients still expect. When you go to a lawyer, you pay for every hour he or she spends, so how can clients keep demanding for changes without paying? Another is free pitching, which has been going on for decades. I had mixed feelings because we participated in them when the studio grew too big at one point. Although it would help us get jobs, it cheapens the profession when we give away our ideas for free, and I have stopped doing it. The third thing is to promote design literacy in society. Clients are unreasonable because they don’t know what good design is. We should be educating the young who will be the next generation of clients.

KC: I recently read an article about how quantity breeds quality. According to the article, Michael Jackson wrote over 900 songs before he arrived at the nine tracks for Thriller. Each of his albums also sounds different because he kept pushing himself to evolve. If you are a true-blue creative, you will always want to try new things. You learn when you experiment. It is also important to have the humility to recognise when your work is bad, and you can do better. If you can’t even discern or be humble enough to acknowledge that, then you will never improve.

At the end of the day, a designer’s role is first and foremost to serve. In my younger days, I tried to push my ideas through, and I forgot to serve my clients. I wore myself out fighting too many battles. But if you accept that your job is to serve, then there are certain things you can let go of. Good design always has to serve something or someone, be it the client or society.

Citation

Jury Citation

Nominator Citation

Nathan Yong

Creative Director

Nathan Yong Design

Kelley Cheng is a unique personality and a tireless proponent of design in Singapore. Over the past two decades, she has created a body of work spanning visual communications, exhibition design and publishing. In 1999, she made a significant contribution to the design industry by founding iSh, a pioneering independent design magazine in Singapore that sought to educate and inspire, as well as promote and support all things design.

The Jury recognises that Kelley has surpassed her primary discipline as a graphic designer and extended her work into a wide variety of domains and disciplines. She is both an ambassador and a provocateur, nourishing culture and pushing the boundaries of design with humility and honesty. As an educator and studio owner, she has worked with many young designers and nurtured the next generation of talents for the good of the wider design community. Her massive body of work is a love story to designers and the design community in Singapore.

The Jury commends Kelley for being a passionate champion of design: an advocate for its power and value, a mentor for new talents, and a generous supporter and voice for fellow designers, architects and artists.

I have known Kelley as a friend and a fellow designer for a long time.

She is passionate about design, and works not just for her client, but first and foremost, for herself. One of her most significant achievements was founding iSh, the first independent design magazine in Singapore that offered a platform to showcase local creativity. Every issue was unique—reflecting her belief in design as a form of art, which she has continued practising over the past two decades.

Kelley’s designs have been profoundly influenced by her love for art, films, music and books. Her works have structure and rhythm like a musical score, and she often includes her own artworks and photographs—demonstrating a rare ability to combine art and design.

Despite her busy schedule, Kelley spends time imparting her knowledge to others. Over the past decade, she has mentored many young designers. She has lectured at conferences, taught in local and overseas institutions, sat on their advisory boards and served as an external examiner.

Kelley’s impressive portfolio and commendable efforts in nurturing the next generation of designers are testimony to her dedication to Singapore’s design industry.