* DESIGN OF

THE YEAR 2020

Cloister House

Designer

Formwerkz Architects

DISCIPLINE

Architecture

DESIGN IMPACT

Advancing Singapore Brand, Culture and Community

Making Ground-breaking Achievements in Design

Raising Quality of Life

CONTACT

From the street, the single-storey house is a modest box compared to its neighbouring mansions. But behind the fort-like walls lie a series of lush courtyards that opens up to different “worlds”.

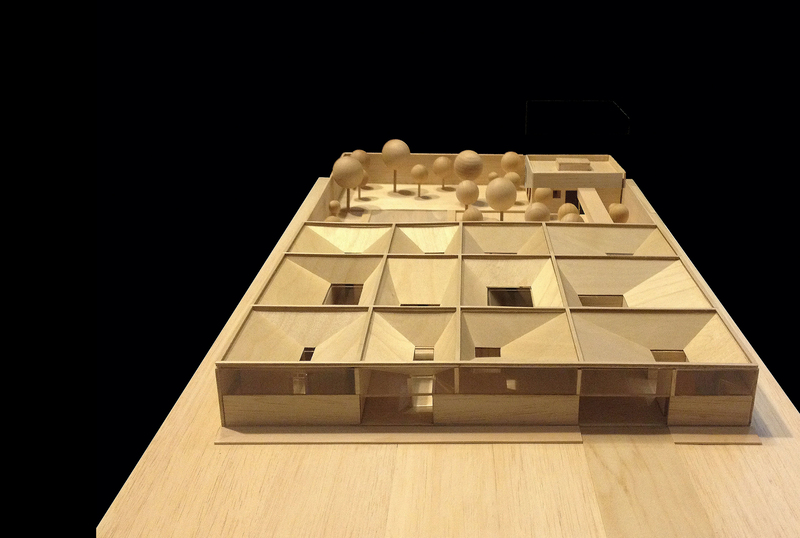

Contained within a generous 4,500 sq m plot–about half the size of a football field – the Cloister House is a large communal living block which leads to a back garden, a pool and a smaller annexe for private bedrooms. The main building has been divided into a grid of rectangles that is punctuated by multiple courtyards, resulting in a maze of different spaces for exploration and entertainment. They are unified by a timber-clad ceiling formed by a topography of inverted pitched roofs. As they fold and flex across the house, the roofs create zones that alternate between lofty and intimate. The ceiling’s skylights also bring natural daylight and ventilation into the deep building, while channelling the tropical rain into the courtyards.

Steadfast in the belief that being grounded is the essence of landed living, the Cloister House pushes against the upward expansion of residential design today. It offers an alternative idea of luxury living in the tropics and new possibilities for the future of landed housing.

READ MOREABOUT THE DESIGNER

Ar. Alan Tay and Ar. Seetoh Kum Loon are the Principal Partners of Formwerkz Architects and the Co-founders of the Formwerkz Collective. Formwerkz’s numerous projects have received critical acclaim around the world, including winning awards from the Architecture Review, Singapore Institute of Architect’s (SIA), FRAME, The International Architecture Award and the Design for Asia Awards.

Both men were also selected in 2010 for the Urban Redevelopment Authority’s “20 Under 45: The Next Generation” initiative in Singapore. Their design approach is shaped by their common interest in examining and establishing relations between man and nature. They believe in the power of design in effecting change and making the world a better place.

Alan is currently an Adjunct Assistant Professor with the National University of Singapore’s Department of Architecture and a member of the DesignSingapore Council’s Design Education Advisory Committee. In 2019, he was appointed by the SIA as the Festival Director of its Archifest. Kum Loon has served as an external examiner for Ngee Ann Polytechnic’s School of Design & Environment since 2012.

READ MOREDESIGN ARCHITECT FIRM

Formwerkz Architects

MALAYSIA ARCHITECT COLLABORATOR FIRM

SH Mok Architect

MAIN CONTRACTOR

Telford Signature (M) Sdn Bhd

Insights from the Recipient

Citation

Jury Citation

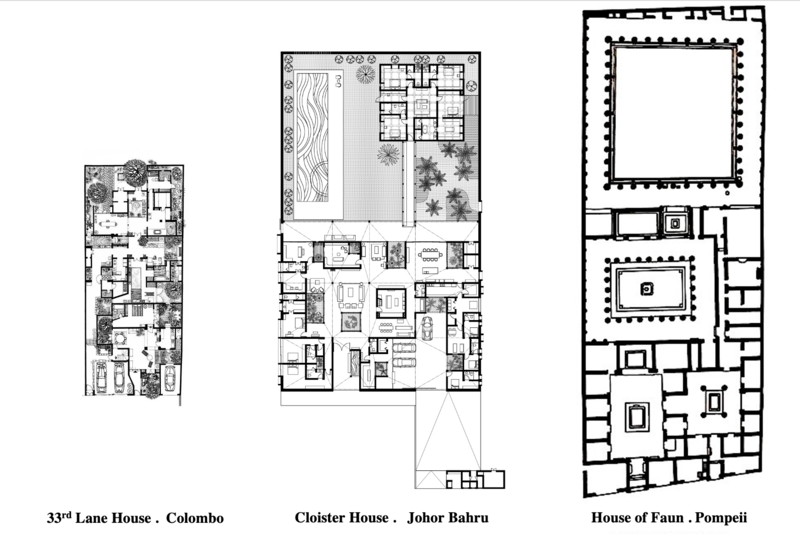

Cloister House is a fresh and artful reinterpretation of the tropical courtyard house.

The one-storey house is composed of a grid of rectangles that is topped by a series of inverted pitched roofs. This creates multiple courtyards and sky wells that shape the internal spatial experience with light and greenery, while allowing fluidity in the organisation of its living spaces. The result is a functional and aesthetically pleasing building that also fulfils the clients’ requirements for a safe and ‘defensible’ house.

The Jury commends the architects for their innovative contemporary reinterpretation of a vernacular design often found in the tropics.

VIEW JURORSNominator Citation

Ar. Yip Yuen Hong

Principal Partner

ipli Architects

The single-storey, shed-like structure that sits squarely in the huge suburban plot certainly looks understated next to its neighbouring lavish mansions. The intricacy and richness that lie within are revealed through the strip of clerestory.

The design makes perfect sense for a large villa that chooses to be fiercely introverted and fortified. It is organised around a system of courtyards, expressed as a structural grid of 12 rectangles. Each courtyard is of a different size, placement and character, giving order to the main house – a microcosm of a city within. This spatial configuration pushes the boundaries of courtyard typologies, creating an interior where the spaces flow fluidly between courtyards and are differentiated by the varying pitches of the undulating roofscape. With a very rigid grid, there could have been a contention that the spaces would be repetitive and boring. But that is not the case. The architects still managed to create masterful, delightful and flowing spaces.

Life within the house revolves around these courtyards. Collectively, they are effective in naturally ventilating and moderating the daylight into the interior. They inspire connection with nature and create a mise en scène within the house. The architects have elegantly fulfilled the family’s needs and aspirations while seeking to expand the limits and interpretations of the contemporary tropical house.