* DESIGN OF

THE YEAR 2018

weatherHYDE

Designer

Billion Bricks Ltd

DISCIPLINE

Product & Industrial Design

DESIGN IMPACT

Advancing Singapore Brand, Culture and Community

Making Ground-breaking Achievements in Design

Raising Quality of Life

CONTACT

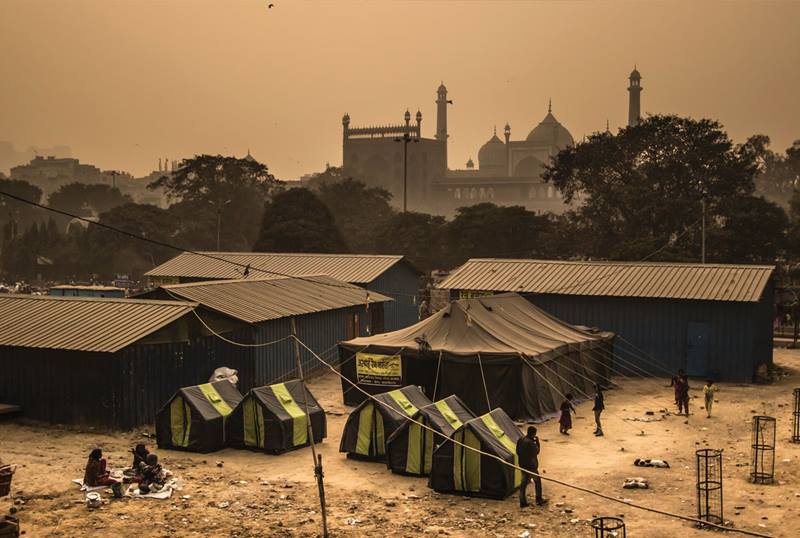

Design a solution that works and the customers will come—even if they are homeless. This is the belief that led to weatherHYDE, an all-season life-saving tent designed by Prasoon Kumar and team at Billion Bricks. Rejecting the traditional view of putting cost at the centre of designing solutions for humanitarian needs, the non-profit design studio came up with this tent for the homeless by treating them as customers who have every right to demand for quality products too.

WeatherHYDE is a shelter made out of an innovative flysheet that protects its users from a variety of elements. A reflective layer traps heat for warmth during winter and reflects solar heat during summer, while the tent’s triple layer skin also blocks light to provide privacy, especially for women, their children and families. Holding up the skin is a sturdy frame that can be constructed with plumbing pipes, eliminating the need for anchors and making the tent ideal for use in the urban environment.

Beyond a product that challenges the traditional sharp divide between needs and wants in humanitarian design, weatherHYDE has an innovative business model where the tents are sold direct to the homeless and to individuals who want to help those around them. This injects a fresh approach to tackling this global phenomenon.

READ MOREABOUT THE DESIGNER

Billion Bricks is a non-profit innovation studio that uses design as its primary tool to solve one of the most pressing global problems: homelessness. It designs and provides shelter and infrastructure solutions for the homeless and vulnerable. These scalable and sustainable solutions create opportunities for homeless families to emerge out of poverty by empowering them to replicate the solutions on their own and reduce dependencies on support. This creates ownership and pride and unlocks untapped potential for change. Since its founding, Billion Bricks has rehabilitated more than 1,800 homeless persons through its work.

The studio was co-founded in 2013 by Prasoon Kumar who is an urban planner and architect with over 10 years of international design experience with his work spanning across Asia, USA, Africa and Australia.

READ MOREDESIGNER

Billion Bricks Ltd

MANUFACTURER

Shenzhen Palm Beach Camping Manufactory Co Ltd

FACTORY

Shanghai Huanxinxi Factory

MATERIAL DEVELOPMENT

Shanghai Brilliant International Trading Co Ltd

Insights from the Recipient

Citation

Jury Citation

The driving ethos of the designers behind weatherHYDE is to end homelessness. Their design is a systems-based solution aimed at making a sizeable dent in this problem. It is a women-friendly, weather-proof, portable and easy-to-set-up shelter for homeless families.

The designers approached their project with a bold, refreshing principle: “Never design poorly for the poor.” The product’s multiple innovations are found in numerous thoughtful details. Inspired by reversible jackets, the tent similarly has a reversible skin for summer and winter use. A new layered stitching method was developed to ensure that the tent remained watertight under extreme weather conditions. An opaque skin protects the privacy of women and children when the tent is lit from within. Even its frame is flexible enough to be constructed out of readily-found materials like pipes or can be 3D-printed. WeatherHYDE is indeed designed with an unwavering focus on its target end-users, whose needs the designers studied through months of interacting with the homeless and volunteering on humanitarian missions in disaster zones.

What further impresses the Jury is the company’s innovative business model, which empowers their users as customers, not beneficiaries. Flexible payment terms allow users to purchase their own tents—homes, in actuality—instead of having to wait for aid. WeatherHYDE is proof that projects with great social equity can improve lives whilst creating value for its users and designers.

VIEW JURORSNominator Citation

Hari Krishnan

Chief Executive Officer

PropertyGuru

Billion Bricks and Prasoon came to my attention in 2015. I strongly resonated with their vision to eradicate homelessness, having grown up in India and seen a number of my countrymen and women struggle to get a roof above their heads.

Having spent time getting to know Prasoon, I saw the story was even better than that. A highly qualified architect and urban planner, he had stepped away from a highly paid job to apply his craft on a worthy cause. Plus, he had done so in the prime years of his career, not after he had made his millions. The sincerity in his eyes and words was unmistakable and his next words made it clear that I wanted to help his organisation succeed. He asked me why someone who is poorer should have a “poorly constructed and designed” house? Why indeed?

Prasoon has a few key elements which any good business leader must have: discipline, a sense of purpose and patience. Having the technical skills to do something about the area he has targeted—putting people into homes and giving them shelter—makes him the ideal leader of Billion Bricks. His solutions focusing on disaster relief (weatherHYDE) and rural self-funding housing (the very exciting powerHYDE) show he is able to connect his purpose with his knowledge.

Having been working with Prasoon a little closer over the last year or so, I have seen some admirable personal qualities which some profess, but he displays: honesty, humility and quiet strength. These are all key in the tough not-for-profit sector and have made him more successful than most.

Billion Bricks is focused on Southeast Asia and India today, but just as easily could impact other parts of the world. Their products are wonderfully portable; as is their thinking.