DESIGN OF THE YEAR 2018

The Future of Us Pavilion

Designer

SUTD Advanced Architecture Laboratory

CONTACT

[email protected]

Why should buildings still be rectangular in shape? This is a question that The Future of Us Pavilion elegantly poses to visitors entering the Gardens by the Bay. The free-form structure—spanning almost 50-metres wide and 16-metres tall—is not just a shimmering entrance into the gardens but a glimpse of what the future of architecture could be.

Located between Marina Bay Sands and Gardens by the Bay, the pavilion sees some 11,000-unique perforated aluminium panels come together to simulate the cool experience of walking under a tropical foliage both in form and function. This is the outcome of Professor Thomas Schroepfer and his team tapping into the power of parametric and algorithmic methods in design from conception to construction. By inputting environmental data from the location, the team used computers to tailor this shelter just for its site. They also factored in the optimum use of materials in order to produce a design that could be built sustainably.

The Future of Us Pavilion is just one possibility from a suite of digital tools the designers created. It demonstrates the potential when disciplinary barriers between architecture, engineering and construction are broken down and information flows seamlessly from one to another. What emerges is a way of design and construction that literally thinks out of the box.

About the Designer

The Advanced Architecture Laboratory (AAL) at the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD), founded and directed by Professor Thomas Schroepfer, investigates the increasingly complex relationship between design and technology in architecture. AAL’s research and design projects relate to advances in environmental strategies, materials, building structure and form, performance and energy, computer simulation and modelling, digital fabrication and building processes.

Prof Schroepfer began his academic career in 2004 at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. He was named Full Professor after joining SUTD in 2011, where he became Founding Programme Director and Associate Head of Pillar of Architecture and Sustainable Design and concurrently serves as Co-Director of the SUTD-JTC I3 Centre. In 2015, he was appointed Member of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Future Cities Laboratory Steering Committee. He has published extensively, including Dense + Green: Innovative Building Types for Sustainable Urban Architecture (2016), Ecological Urban Architecture: Qualitative Approaches to Sustainability (2012) and Material Design: Informing Architecture by Materiality (2011).

DESIGNER

SUTD Advanced Architecture Laboratory

STEEL CONTRACTOR

Protag Tetra Pte Ltd

MECHANICAL AND ELECTRICAL ENGINEER

Engineering Management Solutions Platform Pte Ltd

CLIENT

Ministry of National Development Singapore

MAIN CONTRACTOR

Pico Art International Pte Ltd

CIVIL AND STRUCTURAL ENGINEER

Passage Projects

S.H. Ng Consultants Pte Ltd

WIND TUNNEL CONSULTANT

Applied Research Consultants Pte Ltd

DESIGNER

SUTD Advanced Architecture Laboratory

STEEL CONTRACTOR

Protag Tetra Pte Ltd

MECHANICAL AND ELECTRICAL ENGINEER

Engineering Management Solutions Platform Pte Ltd

CLIENT

Ministry of National Development Singapore

MAIN CONTRACTOR

Pico Art International Pte Ltd

CIVIL AND STRUCTURAL ENGINEER

Passage Projects

S.H. Ng Consultants Pte Ltd

WIND TUNNEL CONSULTANT

Applied Research Consultants Pte Ltd

1For the SG50 celebrations

Located between Marina Bay Sands and Gardens by the Bay, the pavilion was originally built to house The Future of Us , an exhibition to commemorate Singapore’s golden jubilee in 2015.

2Complexity made simple

The pavilion consists of 11,000 unique perforated aluminium panels, 12,040 bolts, 11,188 plates and 4,620 elements for the main steel structure. After the designers set the parameters for the pavilion, they left it to the computers to generate each of the panels which were prefabricated overseas. Everything was then delivered on-site with a map for the construction team to simply put together the pavilion like a giant jigsaw puzzle. The speed and ease of construction impressed the chairman of the

Future of Us exhibition steering committee, Benny Lim: “While most visitors were struck by the finesse and degree of detail of the design, those of us working on the exhibition were more impressed by the ingenious execution that allowed such a complex structure to be constructed so efficiently within a short time.”

3Complexity made simple

The pavilion consists of 11,000 unique perforated aluminium panels, 12,040 bolts, 11,188 plates and 4,620 elements for the main steel structure. After the designers set the parameters for the pavilion, they left it to the computers to generate each of the panels which were prefabricated overseas. Everything was then delivered on-site with a map for the construction team to simply put together the pavilion like a giant jigsaw puzzle. The speed and ease of construction impressed the chairman of the Future of Us exhibition steering committee, Benny Lim: “While most visitors were struck by the finesse and degree of detail of the design, those of us working on the exhibition were more impressed by the ingenious execution that allowed such a complex structure to be constructed so efficiently within a short time.”

Photo by: SUTD Advanced Architecture Laboratory)4Tailored for the site

The pavilion’s unique form is based on the analysis of environmental data such as sun path and wind direction, as well as views from inside the structure. The designers created digital tools that derived forms based on these data while taking into consideration the need to build sustainably with the optimum amount of materials.

(Photo by: fahrulazmi, shutterstock.com)5Tailored for the site

The pavilion’s unique form is based on the analysis of environmental data such as sun path and wind direction, as well as views from inside the structure. The designers created digital tools that derived forms based on these data while taking into consideration the need to build sustainably with the optimum amount of materials.

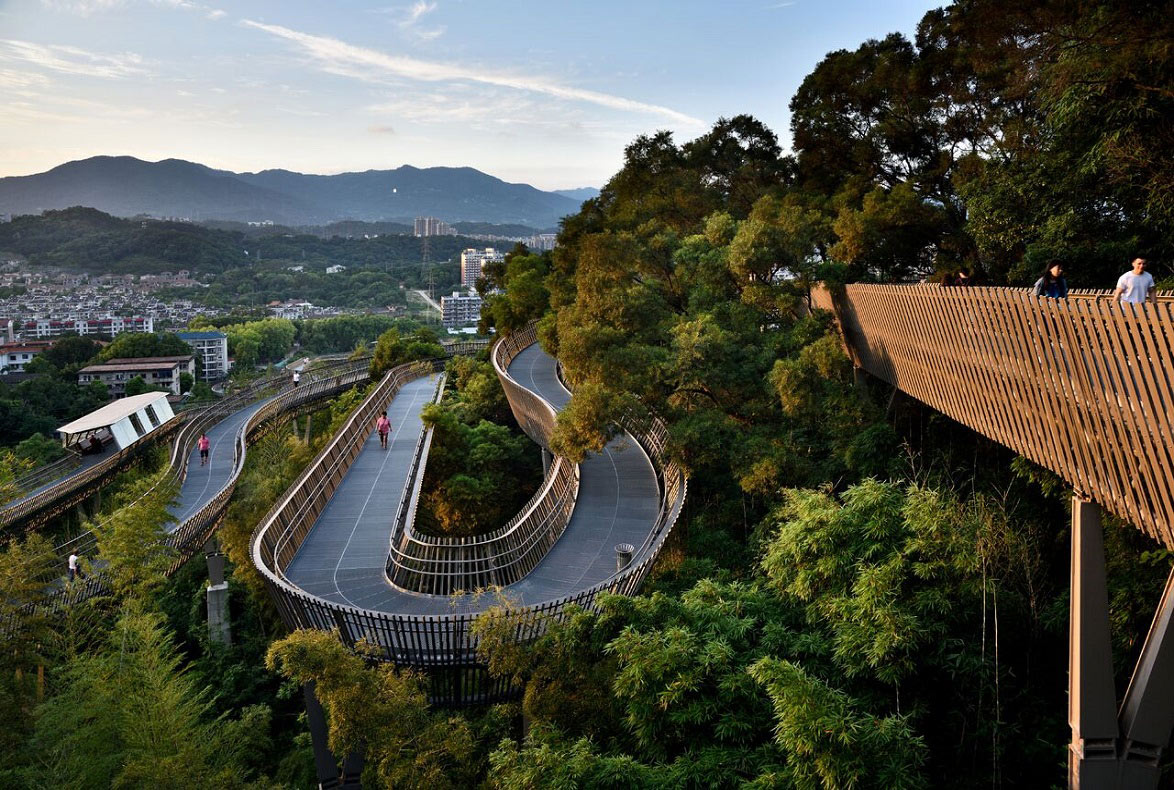

(Photo by: Ng Zheng Hui, shutterstock.com)6Designing a “future nature”

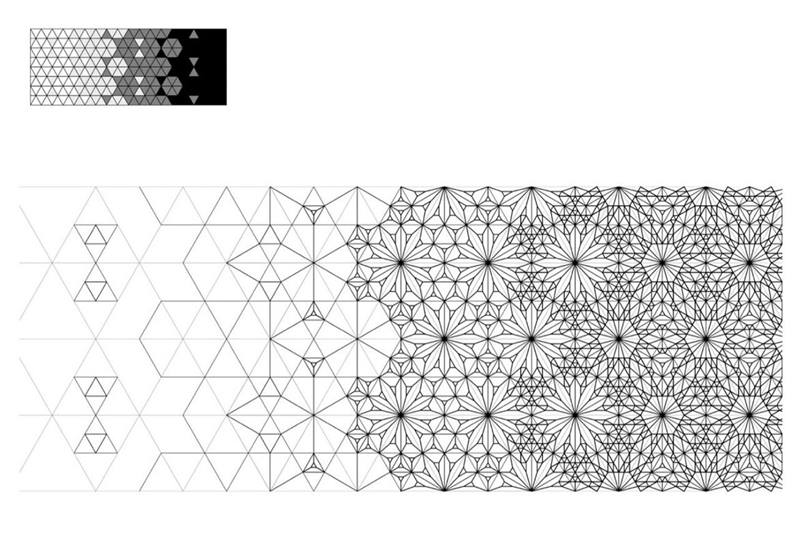

The pavilion is made up of triangular units that become more open and dense based on the need to allow in sunlight, wind and views. Beyond this functional aspect of providing shade, the designers wanted to create a form that mimics walking under the shade of trees in the tropics.

(Photo by: Koh Sze Kiat, Oddinary Studios)7Designing a "future nature"

The pavilion is made up of triangular units that become more open and dense based on the need to allow in sunlight, wind and views. Beyond this functional aspect of providing shade, the designers wanted to create a form that mimics walking under the shade of trees in the tropics.

(Photo by: SUTD Advanced Architecture Laboratory8Home in the gardens

After the Future of Us exhibition, which attracted over 400,000 visitors, the pavilion continued to host a variety of community and cultural events such as the Singapore Garden Festival 2016. It proved so popular that the Gardens by the Bay adopted it as a permanent landmark in 2017 and renamed it the Silver Pavilion.

(Photo by: Guadalupe Polito, shutterstock.com)Insights from the Recipient

Thomas Schroepfer (TS): In 2013, the Singapore Institute of Architects (SIA) ran an ideas competition that focused on parametric design. It is a technique that has been around for a while. For instance, the early projects of Frank Gehry, such as the Walt Disney Concert Hall, exploit the complex geometry that parametric computational modelling allows. What this means is rather than drawing a building, like in the old days, you define a project through computational code that specifies the relationships of one part to another. The whole project can grow, shrink and the geometry can change, but the code and relationships are fixed.

Our competition entry was defined by a computational model that is based on certain parameters we were interested in specific to Dhoby Ghaut Green. We wanted a structure that opens up and becomes denser in relation to sun path, wind direction and views from inside the structure. With a computational model, you can feed in such data about the environment and it would adjust the design of the structure accordingly. It is a highly customized approach where architecture is not a one-size-fits all. Instead, we can create a structure that responds to things that are always there, such as the sun or even shade provided by existing trees.

These ideas remained when we were asked to design a pavilion for The Future of Us exhibition; it is about creating a comfortable experience for an outdoor public space without relying on air-conditioning.

TS: The basic unit of our computational model is a triangle because it is a shape that allows for complex geometries and provides a good structural system. As we feed the algorithm information about the different parameters, we go from a triangle that is almost completely open, to one that gets incredibly dense inside. The design may look very irregular, but it is based on a very clear mathematical logic.

We were also very interested in the visual language that emerges from this model. We describe it as “foliage”—it is like being shaded by the beautiful trees along Orchard Road. The trees make it comfortable to walk on the street, and you also get a beautiful play of light and shadow. So, there is an aesthetic dimension to our model, but it is every much driven by a mathematical precision to 6 work out things like environmental data and structural information.

TS: Shells perform very differently depending on the geometry they have. We created many versions and simulated many geometries to get the optimal design. You can build a shell that is not optimised, but it is going to be much thicker. Our pavilion shell is only about 20-centimetres thick, which immediately translates to how much material we used, the weight of the design, etc. These address ideas of sustainability. By optimizing the design in this way, we made it much cheaper and more effective to build.

TS: When the curators of The Future of Us asked if we could do a pavilion many times the size of what we had proposed for Dhoby Ghaut Green, we said, sure. The parametric model allows not just a change in form but also, to scale up and down. In the conventional model, there is no way you can do this in such a short time and in an entirely different location.

Each panel of our pavilion is constructed from two triangles folded on the edges and then manually put together. Our model is so precise that the top and bottom of every panel are different to further fine-tune their environmental performance. Everything can be different because in the digital environment, the machine does not care. Once we have defined the mathematical relationship, the computer subdivides the design, organises the pattern and so on. We don’t draw every panel by ourselves. Working with a digital model also meant architects and structural engineers were working on the same model and we could feed information directly into the machines cutting the panels. This allowed us to save time.

The pavilion we created was eventually reduced in size not because of the design but simply because production could not keep up. As we don’t yet have a 3D-printer which is large enough to print the pavilion, we had to find a way to make it out of sheet material. We chose to laser-cut triangles out of aluminium sheets; an algorithm was also developed to pack these on the rectangular sheets to generate the least material waste when cut out.

The pavilion was built by workers who had no special training. We provided the contractor with a map of which panel goes where—it is essentially a gigantic puzzle. The panels were all shipped to the site on time and there was no need for storage. There was no sophisticated technology needed for construction. Even the contractor was surprised at how quickly they could put this together.

TS: When tools such as parametric computational modelling first became available, there was a lot of formal experimentation. There was often no performative aspect to it beyond being beautiful. We have since moved on. We can now generate beautiful forms, but we can also make them meaningful. You can put material exactly at the form and quantity that makes the most sense to perform best in the environment.

The true power of this technology is that everything can be customised easily, and it makes no difference. You can design a building quicker than a traditional approach where everything is standardised. This is also the main message: there is absolutely no reason to have buildings that are the same anymore. Our tools allow for very complex geometries so there is no need to have buildings that are all rectangular. There are a lot of reasons why people work with rectangular shapes, but for a project like the pavilion that sits in a landscape— that can be a driver for architecture. Look at the Supertrees or Flower Dome in Gardens by the Bay— their formal language is so different. As Singapore pushes to be a City in a Garden, it should not stop at the level of integrating greenery. Buildings can become landscapes too. This fusion of landscape and architecture is powerful for Singapore because of the climate. Just as airplanes are shaped in a certain way to direct the wind so they can fly, thecity can be shaped in a way to provide a comfortable environment too.

Citation

Jury Citation

Nominator Citation

Dr Tan Wee Kiat

Chief Executive Officer

Gardens by the Bay

The Future of Us Pavilion is a bold move in the Singapore design landscape. The successful form-finding exercise as a means of determining an intrinsically efficient structural and load-resisting form is commendable.

Through the parametric and algorithmic approach, the designers have created a futuristic structure that has pushed the boundaries of design, fabrication and construction methods. The high level of integration between digital technology and building processes allowed for the rapid production of a large number of individual micro-forms that make up the overall structure. The pavilion form also optimises material usage and minimises the embodied carbon footprint. This makes the pavilion a forerunner to many impressive current and future buildings. Such successful utilisation of innovative technologies point the way forward for the industry to adopt similar design and construction methods. In 2017, the pavilion became a permanent landmark in the Gardens by the Bay. It plays host to important public festivals and events, and continues to be well-loved by visitors. This makes it a valuable public asset that contributes to advancing Singapore community and culture.

The Jury applauds the design team for a project that is leading the way towards the future of structure, architecture and design in Singapore and beyond.

Located between Marina Bay Sands and Gardens by the Bay, the pavilion follows the grand tradition of architectural structures that evoke a dialogue between built form and nature in the tropics. Its intricate form and composition, derived from extensive structural and environmental analyses, encapsulate the possibilities that technology already affords us today and hint at the forms we may find more familiar in the years ahead.

Originally built to house The Future of Us exhibition, Singapore’s 50th Anniversary (SG50) capstone event, the pavilion, which we have renamed “The Silver Pavilion”, has since become a permanent landmark that is now an intrinsic part of Gardens by the Bay.

The success factors of the Silver Pavilion are obvious. To enhance visitor comfort in the Gardens, its landforms were designed with wind direction in mind, while foliage and shelter provide as much shade as possible. The pavilion is based on similar ideas. These are beautifully translated into a contemporary aesthetic and functional form. For visitors, the project offers a spectacular experience akin to walking in an imaginary forest—an idea of future nature. The pavilion is a comfortable fit with the Gardens’ Supertrees, domes and canopies. An enthralling vision for a garden of the future is thus encapsulated by its inclusion.

The Future of Us Pavilion, now our own Silver Pavilion, contributes delightfully to the Gardens’ mission of making Singapore a vibrant place to live, work and play. An impressive number of national and international awards and recognitions already attest to the quality and success in realisation of the inspiration behind this newest addition to our Gardens.