DESIGNER OF THE YEAR 2018

Hans Tan

Founder, Hans Tan Studio; and Assistant Professor, Division of Industrial Design,

National University of Singapore

Hans Tan Studio

CONTACT

[email protected]

A chance encounter with a university prospectus led Hans Tan to give up his place in business school and switch to industrial design at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He was intrigued by the school’s definition of industrial design as a mix of engineering, business and design—a formula that Hans has questioned and redefined over the last decade since graduation.

Fresh out of university, he headed to the Design Academy of Eindhoven to pursue a master’s degree as part of the pioneering batch of scholars supported by the DesignSingapore Council. In 2007, he returned home to start his own practice. Inspired by his overseas exposure to conceptual design, Hans began creating his own designs that communicate ideas about the profession and narratives of Singapore’s culture and society. Hans has designed many objects and his experiences have helped others see the profession and the world in a different light. These include the industry, the public and the many young designers whom he has taught as an educator at NUS.

Through his persistent belief in the potential of design as more than just a tool to solve problems, Hans has opened up new opportunities for the profession to demonstrate the many ways it can make an impact in the world.

1Hans Tan

Hans Tan Studio; and

Assistant Professor

Division of Industrial Design,

National University of Singapore

2Spotted Nyonya, 2011

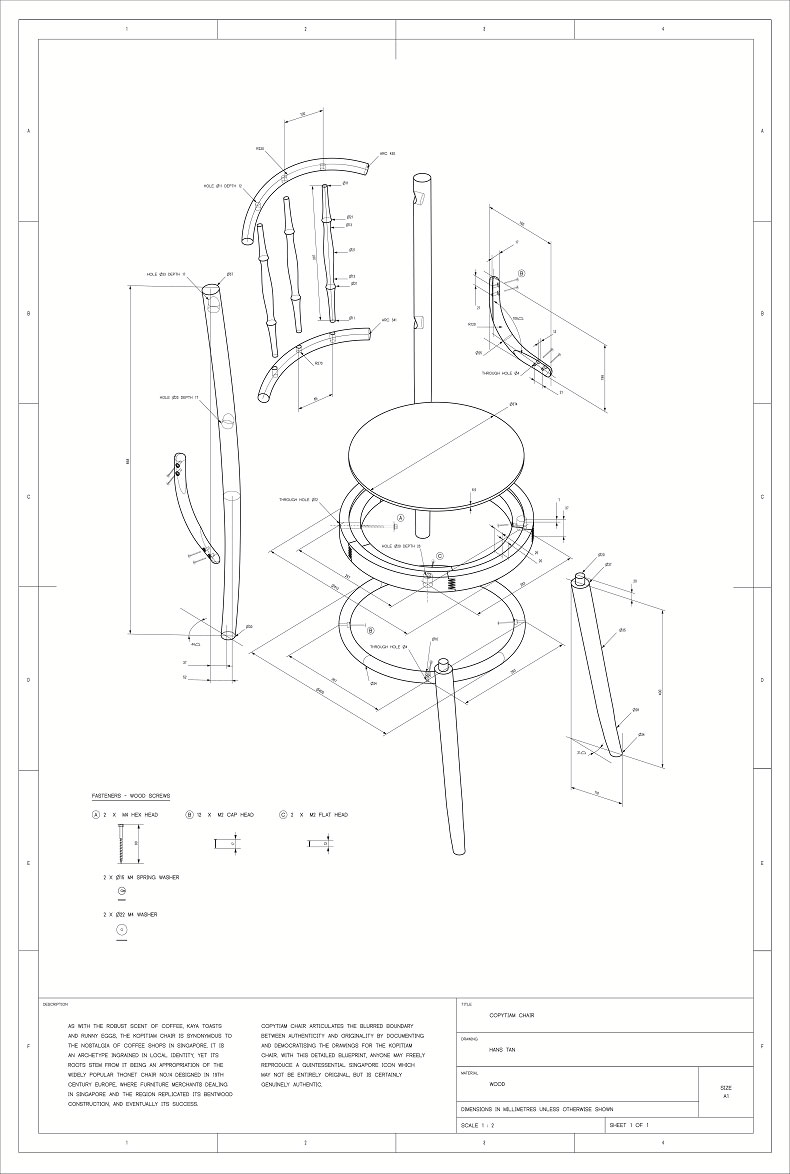

(Picture by: Hans Tan Studio)3Copytiam Chair, 2012

(Photo by: Hans Tan Studio)4Striped Ming, 2013

(Photo by: Hans Tan Studio)5Bundled Vase, 2014

(Photo by: Hans Tan Studio)6Pour, 2015

(Photo by: Hans Tan Studio)7Singapore Blue, 2015

(Photo by: Hans Tan Studio)8Vase Porcelain, 2016

(Photo by: Hans Tan Studio)9No Such Luck, 2017

(Photo by: Guo Jie, Studio Periphery)Insights from the Recipient

The main motivation then was my experience with conceptual design and seeing how artists and designers in the Netherlands used design as a medium. When I came back, there was not much of a movement in terms of people seeing design as not just an end but using it to communicate ideas, especially in product design. Design was a lot less ideological and very focused on the commercial world—being utilitarian and focused on the user. If I wanted to do conceptual design, the only option I had was to set up my own practice. I thought this was important also because design is something burgeoning in Singapore. People have more opportunities to see design, encounter well-designed products and to use design to communicate issues about the world and design itself.

I remember producing an exhibition, V for Vase years ago. An old lady came up to me and thanked the students and me for putting up the exhibition because it helped her see a vase in a way she never knew. This idea of opening eyes and providing a different mode of seeing became something extremely important for me when I produced my works.

We usually see design as something utilitarian. It enables us to sit, travel and pay for things. But design is also a medium that can help people understand the world in a different way. It’s about seeing things differently from how you previously understood it. There are many important issues that one can tag to the things we use. A vase doesn’t just hold flowers, it also talks about the idea of decoration and of it being a vessel or holder. This relationship between decoration and utility is an age-old problem that designers face.

It is also what marketers do. When they sell a car, they don’t just sell you the car but sell the emotions behind it too. Some designers design “emotions” into the product. A fan can look very “technical” if it’s for people who value technicality. A fan can also be designed to be very lifestyle— maybe it looks very breezy and open. Objects have the ability to determine our actions and communicate the way to use them. For instance, different types of door handles will communicate different uses. A long handle may suggest you pull it, but a flat panel may make you push it. This idea of objects communicating ideas is not new at all. What’s interesting is, in actual fact, objects don’t communicate to us. It is what we read from them. We constantly read things in our environment through sight, smell, touch… and as a designer, I use this phenomenon to embed intentional narratives in my objects

Coming from a classical industrial design training, we always talk about the economy of means. It’s about achieving a goal with the least amount of resources. If you design a chair, why not just use one big block of steel? That will never fail. But most chairs we sit on have four legs. Most metal legs are also hollow because you don’t need it to be filled to maintain structural integrity. So, you save material, transportation costs… there are many advantages in being economical. This is inherently buried in my thinking process. Whenever I work on a project, I think about the least you should do. Not just in its materiality but just saying enough for people to understand.

In Spotted Nyonya, I tried to use vases that no one wants to buy or use anymore. When you buy a vase today, you visit a nice lifestyle store but not an old shop in Sims Avenue. I went to these places to pick up vases no one would buy and tried to transform them. This is to communicate how we deal with waste. Something that is termed outdated or ugly in contemporary taste could be transformed and seen in a different light. The transformation is not just to the vase itself but also the traditions and cultures tied to it. Most importantly, my motivation in working with porcelain and ceramics is that I’m not a trained potter. So how do I turn weakness into strength? It’s back to the idea of economy of means and flipping a disadvantage around to see it as an advantage. One of my biggest satisfaction in that series of work was taking a vessel that nobody wanted to buy, not adding anything to it—but in fact removing some material—and selling it for 200 times the price or even to a museum. It shows the power of design is not just an addition, it can be about doing less.

When communicating with design, the easiest way to be understood by many people without a design background is to use archetypes. People understand the world around them through the most common form of objects. The archetype of a cup is the typical broad brim with a narrow base and a handle. If you do something that looks like half a bowl or sculptural, it’s going to be difficult for the user or viewer to allude to the knowledge they have of a cup. If you can allude to the knowledge that the person already has, you can build on the knowledge and create a narrative. That is why archetypes are quite important in my work.

No Such Luck started from my fascination with the Fortune Cat. I found it interesting that many shops here still have the superstition of putting this cat near their entrance to attract business. With the advent of digital technology and seeing how companies use data to drive innovation, I wanted to bring these two opposites together. What if the Fortune Cat’s movement is data driven? This might make businesses question whether the Fortune Cat is really effective in the first place. I installed this for a museum gallery and used the proximity of visitors to the cat as data. When no one is nearby, the cat will swing violently to attract viewers. But as they walk towards it, a proximity sensor will signal the cat to slow down its swinging. This will eventually stop when the viewer is near enough to appreciate the work. People in the museum were disconcerted as an interactive artwork will usually work when you go up to it, but this did the opposite.

One of the biggest misconceptions about design is that designers solve problems, but I think designers find opportunities. That is a more meaningful process. It’s not just about finding solutions to existing problems, but about finding new problems or even finding opportunities to provide changes that don’t stem from a problem. For instance, the disruption of public transportation didn’t stem from solving issues faced by taxi companies. The idea here is how can we see transportation differently and apply the technology of machine learning to drive customer experience and the logistics of a taxi company.

I either start from a material point of view or I work with a point of interest. It’s about finding a meeting point between these two processes. I don’t think any of my projects start from nothing. They are built from previous works based on an overall agenda to investigate various themes and questions related to Singapore’s traditions, cultures and heritage.

Citation

Jury Citation

Nominator Citation

Professor Yen Ching Chiuan

Co-Director

Keio-NUS CUTE Center, National University of Singapore

Hans Tan personifies contemporary Singapore design through a rich and diverse portfolio that is proudly and poetically Singaporean. From his thoughtful reconstructions of Peranakan vases to his downloadable 3D-blueprints for the ubiquitous “coffeeshop chair”—these surprising, delightful explorations by Hans reflect his country’s ongoing search to balance heritage and modernity, craftsmanship and mass production, local concerns and a global vision.

The Jury applauds Hans’ belief to “stay authentically local and the world will come.” His conceptual rigour and innovative processes have resulted in works that are at once artistic and yet firmly practical. Underlying them all is a relentless desire to ask difficult questions about the nature of design: what is its value, meaning, relevance and potential? This is what resonates with the multi-cultural and multidisciplinary Jury, and the museums, galleries and clients around the world who have commissioned him on a wide range of projects. Through his pursuit of Singapore-centred design, Hans has put his home country on the world map.

Beyond the strength of his portfolio, Hans has an equally impressive ambition to transform the Singapore design community through education. As an Academic Head and Assistant Professor for Industrial Design at the National University of Singapore, he has conceived and run courses that use design to achieve creative breakthroughs and has won awards for excellence in teaching.

As a designer who has made significant impact beyond his studio practice, Hans is utterly deserving of this award.

Hans Tan is a designer and an educator based in Singapore. His experimental design works, sometimes balancing on the line between design and art, has pushed the boundaries of design in Singapore, influenced younger generations of Singaporean designers, and advocated the discussion of the Singaporean identity through design and engaged international attention. Hans’ works have been shown in exhibitions such as Singletown at the Venice Biennale, Surface art/design in Dortmund and Cologne, No Boundaries at ArtStage Singapore, and Beauty at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York.

His Spotted Nyonya series was awarded the distinction of “Les Découvertes” (best innovative product) at the fall edition of Maison et Objet 2012 in Paris and also Design of the Year at the President*s Design Award 2012. In 2013, he was named one of Perspective’s 40 under 40, an award that recognises design talent from the Asia-Pacific region. And in 2015, he won the President*s Design Award Design of the Year for the second time with his work, “Pour”. His works are in the permanent collections of M+ Museum for Visual Culture, Hong Kong; Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York; and the Peranakan Museum, Singapore. I believe he is the first Singaporean designer whose work is acquired by the prestigious Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Hans has also actively engaged in curatorial work and design education. He has produced several exhibitions with a keen interest in local design culture. As an assistant professor at the Division of Industrial Design, National University of Singapore (NUS), he has developed innovative approaches to design pedagogy and the student works developed under his supervision have garnered many international awards. He is a three-time winner of the Annual Excellent Teaching Award at NUS and has been placed on the Honour Roll.