DESIGN OF THE YEAR 2025

Silver Pride Lion Troupe

NextOfKin Creatives

CONTACT

[email protected]

One in four Singaporeans will be 65 or older by 2030. If the health and care sectors are to cope with rising demand, it’s vital that people age well. Initiatives have been developed across Singapore’s network of senior centres to facilitate active, healthy, and socially-connected ageing in seniors’ homes and communities. But the programmes on offer don’t always hit the mark in terms of attracting participants: men, especially.

At first glance, the Silver Pride Lion Troupe, a pilot programme for a new form of active ageing, seems counterintuitive. The traditional Chinese lion dance is, after all, an art form typically associated with physical rigour. The hypothesis undergirding the pilot, however, was that a connection with cultural heritage would entice participation in a way that many conventional senior-care programmes did not. After six weeks of engagement and training with seniors from two care centres, this was proven correct.

Of the 30 seniors who trained under the programme, 23 ultimately performed in a HDB void deck at Holland Close for the then Minister for Education, Mr Chan Chun Sing, during Lunar New Year celebrations in 2024. Their rendition of the lion dance, adapted to incorporate wheelchair mobility for the holder of the lion head, involved plenty of pride, but without any jumping, physical strain, or raucous clanging of cymbals.

The Silver Pride Lion Troupe’s equipment and choreography were thoughtfully tailored to the participants’ abilities and needs by a collaborative team consisting of design studio NextOfKin Creatives (NOK) and heritage consultancy Bridging Generations, with input from historic Chinese clan association Kong Chow Wui Koon. By valuing care and respect during the process of adaptation, a beloved cultural tradition was made accessible without compromising its integrity.

The programme ticked all the boxes for active ageing initiatives: physical activity, social interaction, and emotional investment in the process. The most telling marker of its success was the higher rate of male involvement when compared to other programmes at one of the participating care centres.

Regardless of race or religion, lion dance is an art form that resonates with and is deeply embedded in the memories of many Singaporeans. The success of Silver Pride Lion Troupe points to the immense potential for other forms of cultural heritage to introduce a spark of joy to our golden years.

About the Designer

NextOfKin Creatives is a strategic design studio that uses creative thinking to push boundaries and shape the future. NOK believes design is an attitude that empowers positive outcomes.

The multidisciplinary team’s key capabilities include ethnographic research, industrial design, interaction design, motion graphics and animation, digital and physical prototyping, and graphic design. NOK has worked with clients in a range of sectors and been recognised by the SG Mark, Good Design Award, iF Design Awards, Red Dot Design Awards, and DFA Design for Asia Awards – Grand Award.

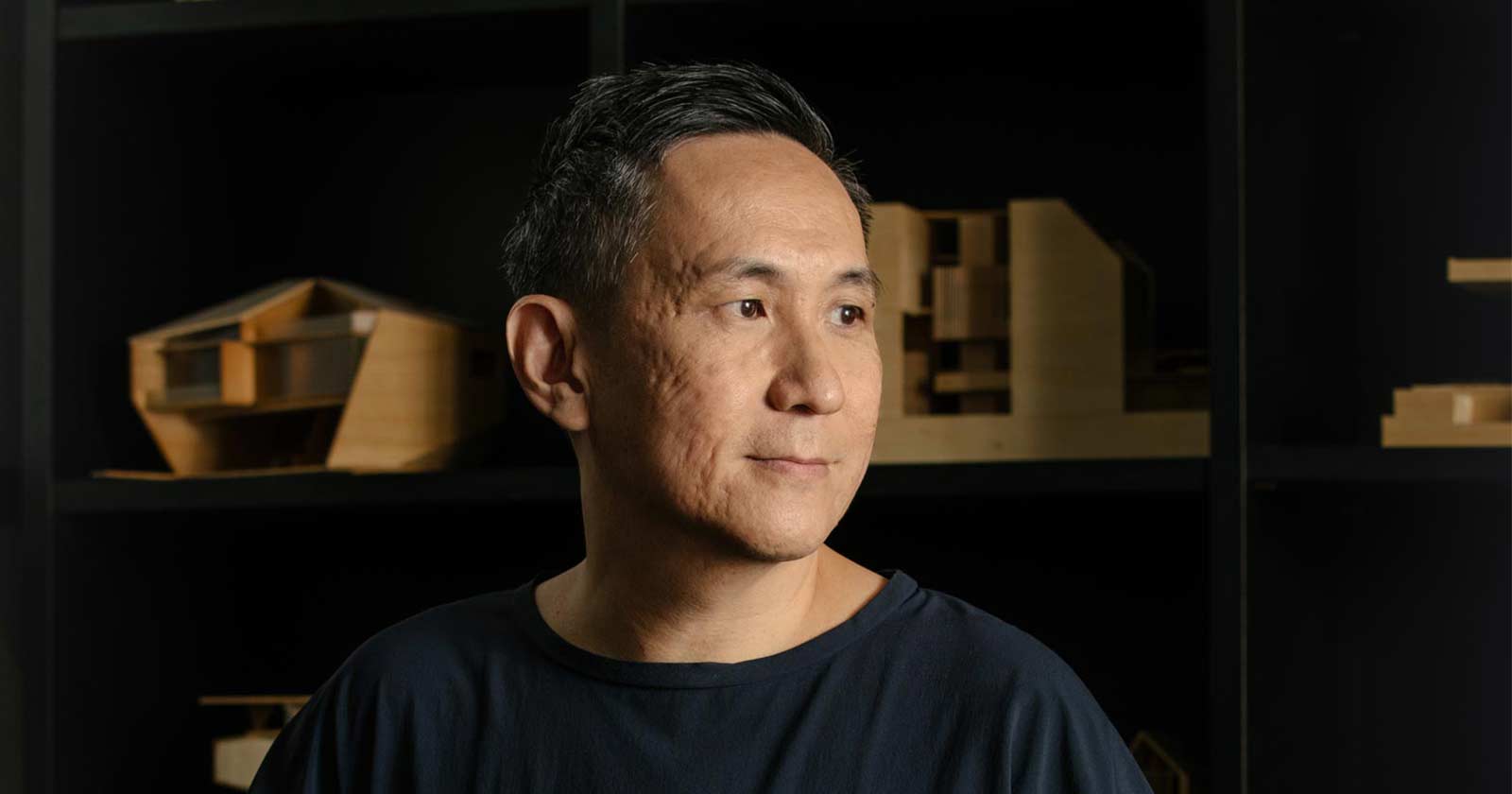

Industrial designer Rodney Loh is the Founder of NOK. He is passionate about creating emotional connections through design. He believes in the power of storytelling to reframe complex issues and bring people together. He sees design as a tool to challenge norms, spark joy, and shape the world we want to live in.

Bridging Generations is a Singapore-based heritage consultancy that reimagines culture for contemporary relevance and social impact. Guided by the ethos “Respect the Past, Move the Present, Inspire the Future”, its interdisciplinary expertise lies in cultural research, design thinking, experience curation, community activation, content development, publishing, and placemaking initiatives.

Bridging Generations has worked with government agencies, institutions, corporates, and community organisations to co-create transformative experiences across diverse sectors such as education, tourism, product innovation, health, and wellness. The consultancy’s notable achievements include DFA Design for Asia Awards – Grand Award, Good Design Platinum Award, UNESCO Storytelling Award, and its flagship Qixi Fest experience that attracts over 180,000 local and international visitors annually.

Lynn Wong is the Founder of Bridging Generations. From transformative programmes that tackle social isolation to immersive experiences that empower seniors, Wong’s ability to bridge generations has made her a powerful voice in preserving intangible cultural heritage through creative, interdisciplinary initiatives. She studied psychology before dedicating herself to heritage work.

DESIGNER

NextOfKin Creatives

Rodney Loh, Sim Hao Jie, Edmund Zhang, Nathaniel Ng, Sheryl Ang, Rayson Tan, Kelly Boon, Nafisah Abu Bakar, Muhammad Haziq Roslany

CLIENT

Lien Foundation

DESIGN PARTNER

Bridging Generations

Lynn Wong

LION DANCE CONSULTANT

Kong Chow Wui Koon

PARTNERING SOCIAL SERVICE AGENCIES

Fei Yue Community Services (Fei Yue Active Ageing Centre, Holland Close)

Yong-en Care Centre

(Yong-en Active Hub)

DESIGNER

NextOfKin Creatives

Rodney Loh, Sim Hao Jie, Edmund Zhang, Nathaniel Ng, Sheryl Ang, Rayson Tan, Kelly Boon, Nafisah Abu Bakar, Muhammad Haziq Roslany

CLIENT

Lien Foundation

DESIGN PARTNER

Bridging Generations

Lynn Wong

LION DANCE CONSULTANT

Kong Chow Wui Koon

PARTNERING SOCIAL SERVICE AGENCIES

Fei Yue Community Services (Fei Yue Active Ageing Centre, Holland Close)

Yong-en Care Centre

(Yong-en Active Hub)

1REDISCOVERING HERITAGE

Thanks to carefully designed tweaks to traditional equipment and choreography, the Silver Pride Lion Troupe pilot programme gave seniors the chance to become lion dance performers in a safe and inclusive manner.

2LOW SOUND, HIGH SPIRITS

Chua Ai Geok, 71, played cymbals modified with felt covers that preserve tactile feedback while reducing noise. The adaptation responds to Singapore’s dense urban environment and protects sensitive ears.

3CULTURE OF INCLUSION

The incorporation of a wheelchair allowed both ambulant and non-ambulant participants to take part in lion dances. Lion dance sequences were adapted with integrity to tradition.

4CROSS-DISCIPLINARY DESIGN

Designers Nathaniel Ng (left), Edmund Zhang (right), and the NOK team worked with heritage consultant Lynn Wong (centre) of Bridging Generations on the project.

5ASSESS AND REFINE

Designer Sim Hao Jie (right) gathered feedback from a senior participant at Fei Yue Active Ageing Centre (Holland Close) during early user testing. The design process involved making ergonomic and mechanical refinements to a traditional lion head.

6FITNESS AND MOBILITY

Wong and Sim consulted with wellness coach Jian Hong (right) at Yong-en Active Hub (Bukit Merah), exploring strength and dexterity training movements that could be integrated into lion dance rehearsal sessions.

7BUILDING STRENGTH

In a training session at a void deck adjacent to Fei Yue Active Ageing Centre (Holland Close), Wong led seniors in seated exercises using hula hoops in place of lion heads. Weights would be added later to gradually build the arm strength needed to lift a lion head.

8ROLLING WITH IT

Wong and Sim used an office chair to test the idea of wheelchair-based lion dance choreography in an early ideation session.

9YOUNGER DAYS

Chia Chiang Teck, 80, lifted the lion head as he familiarised himself with the movements from a wheelchair. Having been a lion dancer in his youth, this moment marked his return to a cherished art form.

10SHARED PRIDE

Tan Sung Ming, 68, practiced his lion dance routine at the final rehearsal before the troupe’s debut. Curious onlookers were drawn by the sound of drums and cymbals.

11PERFORMANCE DAY

For the Silver Pride Lion Troupe’s debut performance, Tan danced with the lion head, supported by a member of the Kong Chow Wui Koon clan association. The cymbals were played by (L–R, back row) Mah Ying Khuan, 99; Chua Ai Geok, 71; and Nancy Choo, 68.

12IN GOOD TIME

(L–R) Choo, Chew, and Chua practicing the cymbals. They were guided by a member of Kong Chow Wui Koon.

Insights from the Recipient

RODNEY LOH (RL): We have always been interested in projects about Singapore’s heritage. In the commercial world, most of our clients’ projects are for electronics, user interface and experience, and innovation. But a few local projects, such as a lantern project with the National Heritage Board, strengthened our belief in using heritage as a form of innovation.

One of our former colleagues, Sim Hao Jie, took part in a design competition in which he reinterpreted a Monkey God statue. That got us connected with Ng Tze Yong. He was from the effigy-making company that organised the competition and also worked at the philanthropic organisation, the Lien Foundation. Tze Yong suggested we look at developing a heritage-related project.

We were thinking about many different pillars of heritage: arts and culture, food, places of worship, and museums. At NOK, we had also been incubating seeds of ideas around intergenerational considerations, active ageing, and even intimacy for seniors. We shared a bunch of ideas with the Lien Foundation. The idea of lion dance was raised by Tze Yong while we were discussing wushu (martial arts) in general. We thought it could be a good way to explore heritage innovation.

LYNN WONG (LW): I’d been in the heritage industry for over two decades, and I’d previously met Tze Yong. I’d also been doing a lot of volunteer work with senior care centres around Singapore, in volunteer management roles. Through that, I was in tune with the opportunities and challenges at these centres.

One of the very salient points I discovered is that, often, seniors are seen as beneficiaries. They are seen as receiving handouts, and that can be very degrading. In looking at the gaps, we realised that, even though Singapore is putting a lot of money into setting up active ageing centres (AACs) in the neighbourhoods for seniors to age in place, a lot of the programmes infantilise seniors.

I’m also a lion dancer and martial arts practitioner. Lion dance is a very versatile art form, offering a variety of different roles that I thought the seniors could take up. I could see how it could be even more empowering, regardless of someone’s physical abilities, if we incorporated a wheelchair.

After being connected by Tze Yong, NOK and Bridging Generations made many visits to AACs. We found out first-hand that social isolation, especially among senior men, is a very real problem. The AACs have no issues attracting women to their programmes, but men tend to be more shy. Lion dance seemed like a very good starting point for attracting men to the AACs.

LW: Usually, people think of lion dance as jumping from pole to pole. We needed to achieve a mindset change. The seniors’ family members might think, “No, Mum, you’ll break a leg.” The AACs would wonder if it was safe enough. The practitioners themselves also had to be on board for this project. In Singapore, there have been previous attempts to innovate lion dance that weren’t well-received.

I happen to be part of a troupe that has a lineage back to the legendary martial artist Wong Fei Hong. One of his third-generation disciples is a veteran of the troupe, and he currently uses a wheelchair. It really helped to bring on board such a respected practitioner. It enhanced the whole story and helped the seniors challenge their own self-limiting beliefs.

RL: We held an onboarding session at the Kong Chow Wui Koon clan association for seniors from the AACs. Lynn prepared a delicious lunch for them and we took a tour of the clan house. We looked at all the vintage lion dance kits and swords. I think that tour brought back a lot of memories for the seniors. Witnessing their passion during that onboarding session gave us the first sign of validation that we were on the right track.

LW: That session was crucial to recruiting the seniors because, back then, even the AACs wondered if there would be enough sign-ups for our programme. People still held on to the stereotype of lion dance being for the young. But seeing is believing. When they saw our master perform the redesigned lion dance choreography for them using a wheelchair, they realised, “Wow, okay, if he can do it, so can I. It seems possible.”

RL: The first thing we did was to modify the existing lion head. We bought one off the shelf and deconstructed it to understand the key mechanisms and touch points. But we were designing it from an able-bodied point of view. Given that many seniors have reduced dexterity, we did our due diligence by making it harder for us to operate, by wearing gloves and so on. But we still needed first-hand information. We passed the lion head to the seniors so they could handle it. We discovered things that we hadn’t previously accounted for such as a difficulty in grabbing the internal strings. The testing with the seniors shaped the refinement process.

It was very reassuring that everyone was keen to have a try. Our participants included a Tamil lady and a Malay lady; it was a novelty for them given how lion dance is a traditional Chinese art form. We also realised that the male seniors were interested in trying it out. That reinforced our hypothesis that lion dance is a very inclusive and active sport which is right for both men and women.

LW: We involved older practitioners in the co-creation of the choreography because they brought a perspective of what the seniors would need. One of the key concerns was fall prevention. We were therefore very intentional about wanting it to be a seated programme, even if people were more ambulant. Safety was the highest priority.

It was very heartening for us, while teaching, to see how this activity was able to bridge different cultures. The seniors were all bouncing along to the beat and very energetic. We emphasised that it’s a secular programme. It’s ultimately part of a culture.

RL: We needed to make it easier to control the lion’s eyes, mouth, and ears. We landed on a single pulley system that you could operate with one hand. You held the lion head with the other hand. We 3D-printed the parts and connected them with levers and strings.

After a few iterations, we managed to get it right. That’s why it was vital to test and validate the modifications with the seniors.

We added tennis racquet grips to the part of the frame that you hold so it became thicker and easier to grasp. The lion head frame has a large diameter, so we added cross bracing so you can also grip the inside of the head instead of the rim. We selected mesh fabric for the exterior to increase its breathability.

We added the same tennis grips to the drumsticks and designed cloth dampers for the cymbals to wrap them and reduce the sound. This made it less overwhelming for the ears. But I think one of the most important parts was creating a troupe name and t-shirts with a logo, so everyone would have a sense of belonging.

LW: We adapted traditions in such a way that the choreography respected heritage and culture while also becoming more inclusive. One of the key modifications to the routine was that the seniors were seated instead of performin athletic moves. We thus focused a lot on the expressions of the lion. How would they express happiness and sadness? What does each of the movements mean? It was storytelling and physical exercise at the same time.

We wanted the training to be progressive so that the seniors could build their strength. We used hula hoops to democratise the exercise classes. Everyone who participated could hold a hula hoop. Our progressive training approach for the dancers involved adding small sandbags for weight. With these little modifications, we could build the seniors’ confidence up enough to ultimately hold the lion head.

LW: I’m most proud that our oldest student, 99-year-old Grandma Mah, was so happy throughout the whole event. We saw how seniors with different abilities found a role and could perform in front of 120 residents. We were able to play to everyone’s strengths and found a way for everyone to feel engaged.

Uncle Chia, who is 80 years old, sat in a wheelchair to perform. It was a huge moment for him. He was almost in tears because he’d had some lion dance experience when he was younger. He never imagined himself performing again because he had injured his leg. His wife was so happy for him.

RL: I saw the enthusiasm of all the seniors, regardless of whether they were Malay, Indian, or Chinese. I saw how the male seniors stepped up. We didn’t need to push them into participating. The energy was very positive. There was a jovial, convivial feeling and that was very touching.

LW: Of course, it’s coincidental that the name Singapura means “Lion City” in Malay. But Silver Pride Lion Troupe showed how this Lion City can also be more inclusive and embrace people of different needs and age groups. This project really showed how heritage art forms can be a solution for a national healthcare issue and can bring the community together. We can leverage what we have to create innovations. Silver Pride Lion Troupe exemplifies that.

RL: Lynn and I were awarded the Design for Asia Award for Silver Pride Lion Troupe in Hong Kong last year. We gave a PechaKucha talk after the event and the most common feedback I heard was, “Hey! Why did the Singaporeans think of it and not the Hong Kongers?”

LW: Exactly! I was so proud!

RL: That was really quite interesting. A lot of the Chinese cultural traditions practised in Singapore originate in China, even simple rituals like having a bowl of longevity noodles with hard-boiled eggs on birthdays. When I post photos of these things on my Instagram account, my friends from China say, “That’s such an old tradition. I’m surprised you still practise this in Singapore.”

In China, after the Cultural Revolution, a lot of things were wiped out. So it was quite interesting and refreshing for them to see such a modern city like Singapore practising these nuances and old beliefs. Singapore is a place where we keep on innovating. We keep on pushing and wanting to punch above our weight. But often, it’s all these little roots, roots of scarcity, roots of ethnicity, that allow us to punch above our weight.

That’s what this lion dance project means to me as a Singaporean. We have all this cultural heritage, with all these passions, nuances, and rituals. If we forget them, then we don’t have a common foundation from which to propel forward while retaining our identity as a multiracial society.

LW: That’s a very good point. The Kong Chow Wui Koon clan association is 185 years old. Its founding is much earlier than Singapore’s independence. The project shows how we have made something historic not only relevant but also able to solve the pressing issues of today.

LW: To scale it in Singapore, it needs to be medically evaluated and have its healthcare outcomes validated. That’s the next phase I’m looking into. One of the key issues of implementation is having enough practitioners in order to scale. We’re looking into how to leverage technology to codify intangible cultural heritage.

RL: If you could gamify the percussion on a TV screen with a drum set, that would really allow more seniors to engage.

LW: Yes, it would help to streamline the teaching process and curriculum and ultimately enable a roll-out all over Singapore.

Citation

Jury Citation

Nominator Citation

Lee Poh Wah

CEO, Lien Foundation

Silver Pride Lion Troupe is a groundbreaking initiative that redefines active ageing by integrating Singapore’s cultural heritage into senior engagement. By adapting lion dance – a tradition deeply rooted in physicality and community – the project provides an innovative and culturally resonant way to promote physical well-being, social connection, and skill-building, particularly among hard-to-reach male seniors.

With a thoughtful and inclusive design process, including physiotherapist involvement and adaptable roles, the initiative ensures accessibility across different abilities while challenging the infantilisation of senior care. The team’s sensitivity to tradition, coupled with their agility in addressing gaps, allows the project to bridge generations and formalise cultural practices in new, meaningful ways.

Beyond its immediate impact, Silver Pride Lion Troupe addresses broader societal stigmas surrounding ageing, fostering a sense of belonging and empowerment among participants. Its community- driven approach and scalable model offer potential for replication both locally and internationally, making it a powerful and culturally significant contribution to rethinking ageing in modern society.

As Singapore ages, our care economy needs to transform. The Silver Pride Lion Troupe demonstrates how this might be done. It used design to identify and unlock underutilised assets from adjacent sectors, in this case cultural heritage, in a win-win manner. It attended to the physical, emotional, and social needs of our seniors while simultaneously reinvigorating our dying cultural traditions.

Among Singapore’s myriad traditions, lion dance has universal appeal. Its configuration also allows for a variety of roles to fit seniors with different residual abilities. It is associated with joy, vitality, and community: the ingredients of a good life.

Silver Pride’s seemingly humble output, a troupe of amateur white-haired lion dancers performing in a HDB void deck, belies the design challenges it overcame. For designers in a multiethnic nation like Singapore, cultural heritage can be risky terrain. Good intentions don’t matter; get the balance just slightly wrong and the public, if not the law, can come down hard. Past efforts to reimagine lion dance, an ancient art form cherished and guarded closely by both practitioners and the public, have not always succeeded. The very step of beginning Silver Pride, therefore, is not to be underestimated.

In the end, the project succeeded because the team practised the best principles of design: inclusion, functionality, and balance. It exercised courage with restraint, imagination with respect. As a result, the redesigned equipment and choreography were not only accepted but were embraced by all stakeholders: master practitioners, performing seniors, social service professionals, and the heartland audience who attended its maiden performance.

Media outlets competed against each other to gain exclusive behind-the-scenes access to document the two-month training programme leading up to the performance. Coverage was generated in both mainstream and non-mainstream news media locally, as well as international media like AFP. Comments on social media were enthusiastic; many never imagined something like Silver Pride, yet they intuitively understood what the team aspired to achieve.

The team that co-created Silver Pride was diverse, comprising professionals from disparate disciplines such as industrial design, cultural heritage, and social services. The Lien Foundation helped to bring private sector companies (design studio NextOfKin Creatives and heritage consultancy Bridging Generations), a 184-year-old (at the time of writing in 2024) Chinese clan association (Kong Chow Wui Koon), and social service agencies (Fei Yue Community Services and Yong-en Care Centre) together. The team was intergenerational, with designers in their 20s and 30s working alongside lion dance master practitioners in their 70s.

For a male-dominated art form where, historically, women’s participation was taboo, the project’s gender representation is worth noting. The team’s domain expert on lion dance was Lynn Wong, the 30-something-year-old boss of Bridging Generations. Many of the leaders and professionals at the social service agencies championing the programme were women. So too were many of the performing seniors. The project showed some of the surprising ways in which design can connect communities.

In Silver Pride, we see expressions of the unique Singapore story: there were seniors of different races and religions performing harmoniously together in a Chinese lion dance troupe; a modern city, barely 60, already learning how to treasure its history; a caring societ whose younger generation is using design to help seniors in unique ways; and of course, the cute, cloth-wrapped “low-noise cymbals”. Only true-blue Singaporeans know how much we hate noise.

In the end, the trojan horse was a lion. What Silver Pride demonstrates is that what is possible with lion dance may also be feasible with other aspects of our cultural inheritance: food, music, and craft from across races and religions. For this, we hope the President*s Design Award 2025 jury will offer its recognition and support of the team’s work.