DESIGN OF THE YEAR 2025

Delta Sport Centre

Red Bean Architects

CONTACT

[email protected]

Since 1979, the Delta Sports Complex – now known as Delta Sport Centre – had served the communities of Redhill and its surrounds while also hosting professional and international competitions. The unassuming modernist-inspired architecture, originally designed by the HDB, stoically persisted even as the newly opened East-West Line of the MRT network obscured its street presence in the late 1980s.

Local residents continued to enjoy the sports amenities like facilities for swimming, hockey, and badminton. However, given the changing demographic in the area and the relocation of professional sports matches to other locations, Sport Singapore recognised the need for improvements to the Delta Sports Complex.

The firm appointed to design the new alterations and additions, Red Bean Architects (RBA), saw much greater potential than what was outlined in the brief. Alongside the chance to thoroughly enhance the experience of the Complex, RBA saw the project as a prime opportunity to showcase the potential of a thoughtful approach to adaptive reuse.

RBA wished to respect the old buildings, even without the presence of official heritage protections, but without being confined by a single-minded approach to preservation. In RBA’s view, responding to community needs meant not being afraid to update the buildings. Crucial to their intervention, however, was the belief that the strength of the original architecture should still be discernible after the change. The buildings should not look entirely new.

Another of RBA’s critical insights was their consideration of the site as a piece in an urban puzzle. The studio’s incising of perimeter openings and the addition of an elevated linkway stretching across the site were instrumental in connecting the disparate parts of the Complex and stitching it to its surrounds.

Additions, such as a new elevated gym above the teaching pool, were balanced with subtractions like the removal of under-utilised tiered seating. Bearing a now-characteristic deep red colour, Delta Sport Centre establishes a new presence facing the Redhill estate. The project demonstrates that recognising, celebrating, and thoughtfully reusing our architectural heritage, no matter how modest, can yield numerous benefits.

About the Designer

Red Bean Architects LLP was established in 2009 by Ar. Teo Yee Chin as a sole proprietorship, and converted to an LLP in 2020 with Ar. Zeeson Teoh as Partner. RBA’s portfolio includes private residential houses and interiors; public projects in the civic, educational, and institutional domains; and adaptive reuse projects.

RBA takes a humble, technical, and deeply contextual approach to the design of buildings, seeking to understand the wider social, cultural, and urban context of each project to anchor them in place. While appreciative of history and heritage, RBA believes the evolution of society and the city demands that buildings adapt and respond to stay relevant.

Teo, Managing Partner of RBA, is an architect and geographer. He graduated from architecture at NUS in 1996 before obtaining his Master of Architecture from Harvard Graduate School of Design in 2003. He completed his PhD studies in geography at NUS in 2025, focusing on the fields of agri-food networks, political ecology, and political geography.

Critical writing about the city is an important complement to Teo’s creative practice. From 2017 to 2020, he was Chief Editor of the journal The Singapore Architect. Increasingly, he looks at design as a matter of simply seeing and understanding the conditions that constrain us, then finding a way of overcoming them.

Teoh, Partner of RBA, studied architecture at RMIT University and achieved his master’s degree in 2012. He joined RBA in 2013. He has experience in designing and managing private landed residential projects, ranging from terrace houses to good class bungalows, as well as public projects.

Teoh draws deep meaning from working on the adaptive reuse of civic architecture. Creatively reinterpreting these spaces to preserve the city’s history, while meeting evolving needs, is a privilege that allows him to contribute to the community through architecture.

DESIGN ARCHITECT FIRM

Red Bean Architects LLP

Teo Yee Chin, Zeeson Teoh Sau Wei

CLIENT

Sport Singapore

CIVIL AND STRUCTURAL ENGINEER

C P Lim & Partners LLP

LANDSCAPE CONSULTANT

Chig Landscape Architecture

MECHANICAL AND ELECTRICAL ENGINEER

Unipac Consulting Engineers LLP

QUANTITY SURVEYOR

BCM Consultants Pte Ltd

MAIN CONTRACTOR

Hua Keong Industries Pte Ltd

DESIGN ARCHITECT FIRM

Red Bean Architects LLP

Teo Yee Chin, Zeeson Teoh Sau Wei

CLIENT

Sport Singapore

CIVIL AND STRUCTURAL ENGINEER

C P Lim & Partners LLP

LANDSCAPE CONSULTANT

Chig Landscape Architecture

MECHANICAL AND ELECTRICAL ENGINEER

Unipac Consulting Engineers LLP

QUANTITY SURVEYOR

BCM Consultants Pte Ltd

MAIN CONTRACTOR

Hua Keong Industries Pte Ltd

1ZIG-ZAG MOTIF

Concrete fins on the new elevated gym block shield the interior from the sun. Glazing faces north and south to allow natural light to penetrate with reduced heat gain. The zig-zag motif echoes the existing architecture.

2NEIGHBOURHOOD PRESENCE

The gym block appears to hover above the rising MRT viaduct alongside Tiong Bahru Road. The horizontality of this community space provides a counterpoint to the verticality of the surrounding residential towers.

3OPEN AND CONNECTED

The facade of the indoor hall block was opened up with new glazing. The adjacent driveway and parking area were paved to form a traffic-free route to the nearby bus stop.

4FITNESS OF FORM

The main entrance and drop-off zone is framed by the elevated gym block. The elevated promenade connects to the adjacent pedestrian bridge that crosses Tiong Bahru Road.

5STITCHED TOGETHER

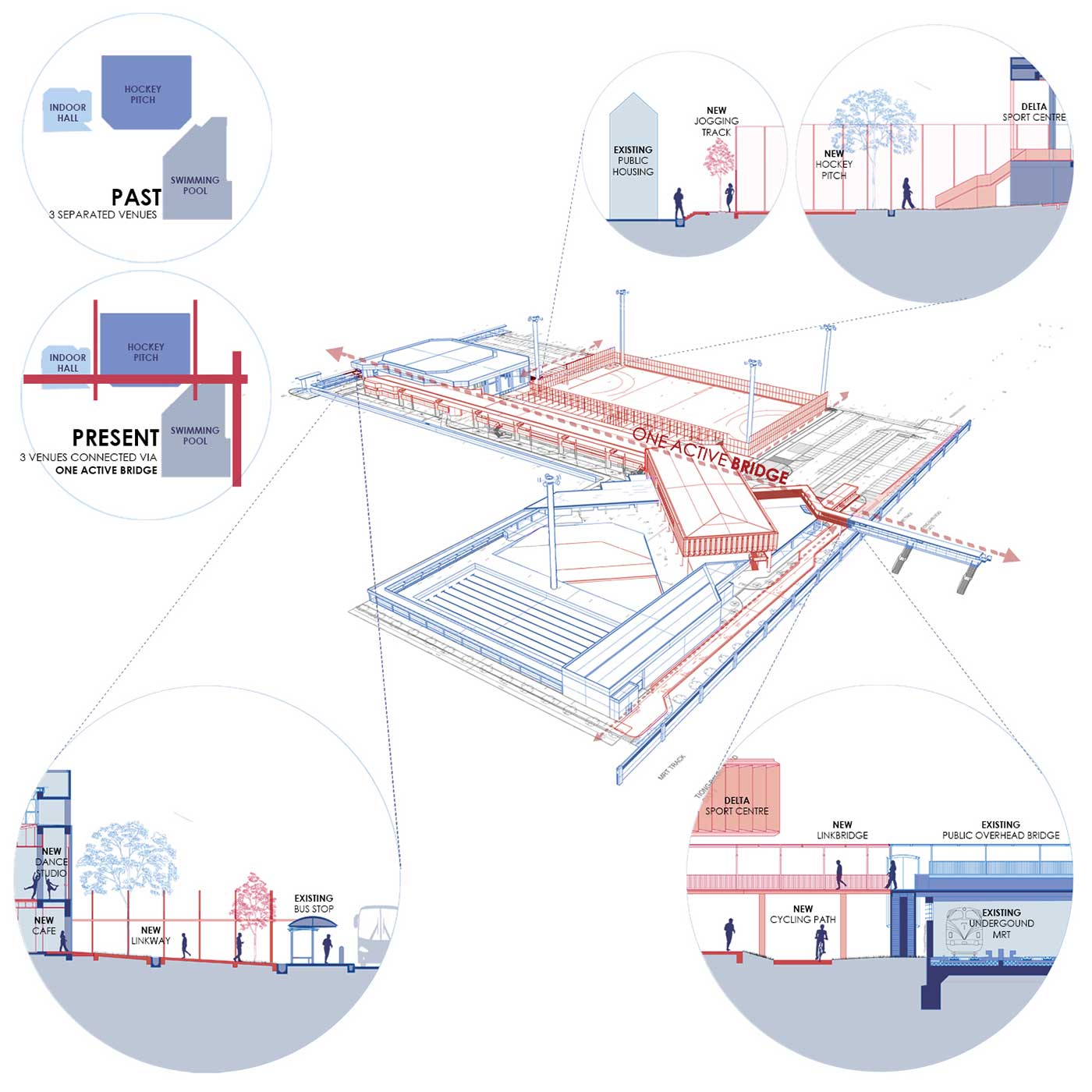

Drawings indicate how the existing buildings and facilities are stitched together by new circulation routes that also connect with the surrounding neighbourhood.

6SHELTERED ASPECT

The gym block shelters a teaching pool as well as the route to the entrance reception. A jogging track meanders through this double-volume space below the second-storey promenade.

7FLOW OF TIME

Diving blocks with eye-catching numbers set in mosaic tiles were preserved at the swimming pool. They forge an obvious link to the decades-long history of Delta Sport Centre.

8UNHINDERED SPACE

The zig-zag motif returns in the indoor hall, which is primarily used for badminton games. Some stepped seating was removed to provide space for two more badminton courts, a dance studio, and a cafe.

9LIGHT MOVES

The new dance studio benefits from a new full-height glass facade looking out to Alexandra Road. Mature trees here were retained to provide shade and character.

10SELECTIVE SUBTRACTIONS

The removal of walls around the staircase at the indoor hall allowed the architects to articulate contrasts between solids and voids, revealing diagonal features in the existing building.

11PROMENADE WITH VIEWS

What was previously the top step of the concrete stadium seating has been reimagined as an elevated promenade that connects the swimming complex to the indoor hall. It overlooks the courts below.

12LIGHT BOX

The gym block replaces what was formerly a shelter above a wading pool. Its sunshading fins establish a rhythm across the facade.

13CHANNELLED ALONG

The concrete stadium seating was reimagined as an elevated promenade that connects the swimming complex to the indoor hall. Chains direct rainwater from prominent V-shaped spouts to drains below.

14RIGHT ANGLE

The angled concrete sunshading fins are set at a 45° angle, facing east or west depending on which facade they are on. The glazed panels are installed perpendicular to them.

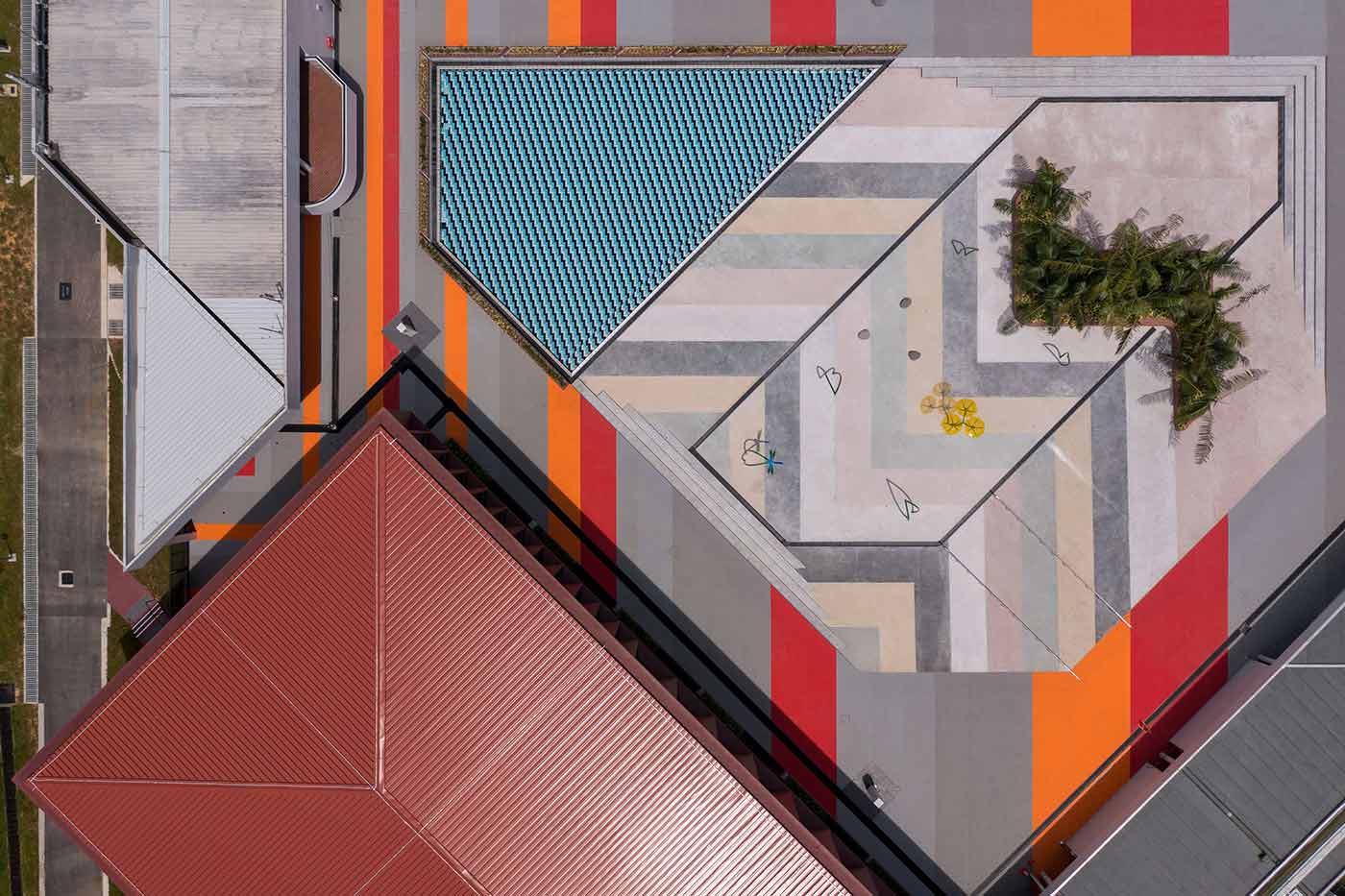

15COLOUR FIELD

The zig-zag motif also features on the paving and planter around the swimming pools, providing a striking view from above.

Insights from the Recipient

TEO YEE CHIN (YC): Delta Sports Complex was built in 1979 and underwent a fairly major Addition and Alteration (A&A) process in 1991. Back in 1979, Singapore was still quite a young nation and the estates around the building were not as mature as we see today with their ageing demographics.

Back then, the new sports facility was state-of-the-art. It was a competition venue. Aside from the pool facilities, there was a hockey pitch and badminton hall with spectator seats quite well provided for. Astroturf was installed in 1991 and the hockey pitch was used for national tournaments. The Women’s National Team won gold there in the 1993 SEA Games.

Now, there are better, newer, and more advanced facilities such as Singapore Sports Hub. Delta Sports Complex evolved into a familiar community space and took on a different character. Since it’s nestled within housing estates, there’s always been a good pool of users.

YC: We didn’t set out thinking, “What’s the identity of this project?” That usually comes later. We always start with spatial quality and functionality. However, we also always have emotional attachments to buildings and places. I used to play hockey at Delta Sports Complex as a schoolboy. My memories of going there gave me a very personal connection to the place. I think this helped us to bring a very empathetic attitude to designing this place. I also had knowledge of how people used to navigate through the building.

ZEESON TEOH (ZT): I define the identity of a building as its presence within its context. Since we rejuvenated Delta Sports Complex, I’d say its presence has become more developed. To me, the community around Redhill now has something that is much more connected to their area. I hear people on the ground refer to Delta Sport Centre as “the red block buildings”. This creates conversation, which is great.

YC: The three parts of the Complex – the swimming facilitites, the hockey stadium and the badminton hall – are now more integrated. Our hope is that this integration as one complex allows the surrounding communities to connect around it. If you view Delta Sport Centre from Alexandra Road now, you can probably mentally link it to the Tiong Bahru side. I don’t think that used to be the case.

I don’t know if I would use the term “landmark”. I think we just wanted people to be able to see it and know how to access it, when even that was difficult previously.

ZT: From a macro point of view, the first thing we wanted was to create connections with the surrounding context. We created the link bridge that connects with a public overhead bridge on the Tiong Bahru side. From there, it links to the hockey pitch at the heart of the complex and through to the Alexandra side at the other end. There’s more public housing on the Tiong Bahru side and more private housing on the Alexandra side. The bridge and linkway stitch them together.

We also tried to dissolve the hard boundaries along the east and west. Previously, Delta Sports Complex was more gated, in a sense. You could only enter from the Alexandra side or the Tiong Bahru side. In our new proposal, we suggested removing all the fences and introducing more physical and visual entry points.

Now, Delta Sport Centre is more porous and boundaryless. You can even see people wearing slippers taking an evening stroll through the Centre. With the idea of stitching it to the surrounding context, the whole sports complex has become a community space catering to sports users as well as residents from the neighbouring areas.

These urban stitches were less about dramatic interventions and more about considerate incisions. We tried to connect across roads, remove obstructions, and create more layering of circulation so people can engage with the site in a way that’s natural, intuitive, and inclusive.

YC: The site presented certain opportunities. Given the levels of the hockey bleachers and the badminton hall, it made sense to connect them with a bridge. That led to the idea of building a gym over the teaching pool. From there, the thought of connecting to the existing overhead bridge became really exciting. We took inspiration from what was already there and extrapolated it. We brought a more ambitious urban outlook to the project, whereas the brief was primarily focused on functional upgrades for the facilities.

YC: The eastern edge of the site, which faces the old Henderson Crescent flats, was previously the hardest edge because of the hockey field. Hockey can be a dangerous sport because the ball is small and very hard, so the fences need to be tall. The hockey fence used to double up as the boundary fence, so pedestrians couldn’t filter through.

We moved the tall fence inwards to the edge of the minimum buffer space around the playing field, according to regulations. That allowed us to remove the boundary from the edge of the site.

YC: We had the freedom to make those judgments and I was happy to be the person who had the prerogative to do so. I don’t believe that all buildings need to be handled like jewels. The people using them can change, and the surroundings change with them. I feel that we need to keep our eyes peeled, to see what new things need to be done, so that a building can adapt to the changing conditions while retaining its familiarity.

Here, one of our guiding parameters was spatial quality. For example, we explored the possibility of removing some floor slabs to make double-volume spaces within the structural constraints. Visibility and accessibility were also important considerations. For instance, we decided to take out a brick infill wall that faced Alexandra Road. It used to be just a blank facade, which was such a waste because it was facing the main road. It was quite an easy decision to glaze it. All these very basic moves made a big impact.

We saw a lot more of the existing architectural qualities once we started peeling layers away. We were able to articulate certain features like the detailing of the reinforced-concrete parapet of the staircase facing Alexandra Road; it has these articulated indents that gelled well with the rest of the architecture. The diagonals worked well with the giant V-shaped spouts, so we saw the opportunity to open that stairwell up to reveal them.

ZT: The rear of the indoor hall used to be very monolithic. We had a vision of that rear building being a key entry point for the Henderson Crescent side. The simple gesture of opening the facade up and removing slabs to create a double-volume space made everything look more welcoming. A lot of our design gestures were about doing as little as possible, but making it very effective.

YC: Bukit Merah means “red hill” and the site did have red earth. There was a brickwork factory nearby, in Queensway, which used the local clay to make bricks. We decided to play it up by using a brick colour. If you look around the site, some of the HDB blocks there do the same.

ZT: We have observed a noticeable increase in use. Previously, there was no jogging track. It was part of the brief to include one, but we expanded it and created a jogging track that runs across almost the entire site. Every time I’m there, I see different people using it – including seniors wearing slippers and strolling there. It’s not just serious runners. I think that’s great because it really shows that we managed to integrate the Centre with the surrounding community.

The bridge spine was the most successful community space that we created on the site. People use that space as a thoroughfare, as a meeting point, and even as a place to pause and linger because you can stand there and watch the games below. It’s not just a walking space; it’s a community space that we indirectly created.

YC: Previously, most activities happened inside the buildings. The change now, is that because we opened things up and created these linkages, the circulation animates the space. It becomes a character of the architecture.

YC: Well, the architectural community would take a different message away than the community of people who use the building in their everyday lives. That message would be that not everything needs to be torn down. Familiarity is meaningful to residents. The removal of a building that has stood beside them for a very long time can be a noticeable change in their environment. I feel strongly about this and I hope the professional community can take inspiration from this example.

ZT: When I first started working in architecture, I thought A&A was very challenging and that it was difficult to add value. Going through the process of this Delta project, seeing how it’s been built, and finding outcomes, made me realise that there’s actually a lot of value you can add. You can rethink everything.

These A&A projects, especially at this time, really help send a message that all buildings can work well if they’re approached in the correct manner. It’s the intervention that’s important. Balancing the existing with the new intervention is crucial to making projects meaningful. It’s not just a matter of retaining everything.

YC: You need the creativity of the architect to do this kind of project because it’s very intricate. You have to go in and see what the opportunities are, see what you can do in each micro situation. Then you have to think across scales.

With regard to the message that the residents might receive from the architecture, I hope they see that it’s now more of a connecting space for different members of the community. There are high-end condominiums and public housing blocks around the Delta Sport Centre. I hope it enables all the residents to come together and meet each other. I hope they realise that this kind of building can also be a community space. I hope they can see the possibilities of architecture.

Citation

Jury Citation

Nominator Citation

Teng Geok Seng

Partner, C P Lim & Partners

Delta Sport Centre is a successful adaptive reuse project that creates impactful outcomes for its surrounding communities by retaining and re-using existing structures with small, deliberate design interventions. One of the key interventions is a second-storey thoroughfare that connects the development seamlessly with its surroundings. Linking the sport centre directly to existing overhead bridges, the nearby MRT station, and the bus stop, this distinctive thoroughfare is clear and well-managed, serving as a connecting node for residents living at opposite sides of the sport centre.

Sports facilities such as the swimming pools, hockey stadium, and badminton hall, which were previously operated separately, have been brought together into one cohesive complex. The jury applauds the architect for the thoughtful design which cleverly stitches and enhances the urban fabric with an engaging sport centre in response to the changing social and physical contexts.

I am delighted to provide this reference for Red Bean Architects in their bid for the President*s Design Award Design of the Year, for Delta Sport Centre. I had the privilege of working closely with the Red Bean team as the structural engineer on this project.

I still remember the old Delta Sports Complex, that we were all familiar with, before the rejuvenation was done. Over the years, the facilities became outdated and many people started to use newer facilities elsewhere instead. The construction of Redhill MRT also cut Delta Sports Complex off from the surrounding neighbourhood.

With the rejuvenation, one of the key changes Red Bean Architects made was the effective introduction of the new “One Active Bridge”, bringing people from Tiong Bahru Road across to Alexandra Road and vice versa. Delta Sports Complex has transformed to become not only a central activity hub for sports, but also a key thoroughfare for connectivity within the neighbourhood. It has provided residents with not just a renewed sports facility, but also better accessibility within the neighbourhood, enhancing and bringing greater convenience to their daily lives.

Aside from Delta Sport Centre’s positive impact on residents’ lives, this project has also set a new standard for the adaptive reuse of old and outdated buildings in Singapore. It proves that many of such old buildings do not need to be demolished and can be innovatively transformed through strategic adaptations. The best way to be sustainable should be to reduce unnecessary reconstruction and to consume fewer resources.

This project deserves the Design of the Year accolade because of its exemplary use of simple moves to create impactful outcomes for the community. The thoughtful interventions have breathed new life into an obsolete sports facility, transformed it into a new landmark, and impacted the use of the surrounding neighbourhood. It stands as a model for future projects.