DESIGN OF THE YEAR 2025

21 Carpenter

WOHA Architects

CONTACT

[email protected]

The past breathes into the present at 21 Carpenter. This boutique hotel on the fringe of Chinatown consists of four carefully conserved shophouses dating back to 1936, and a striking new block that cantilevers over the heritage buildings. The new extension is a Jenga-like form of stacked cubic volumes that reveal and frame elements of the old building. The perforated facade of the new block incorporates the sentiments of migrant workers from years gone by in the form of phrases of reflection and longing for home.

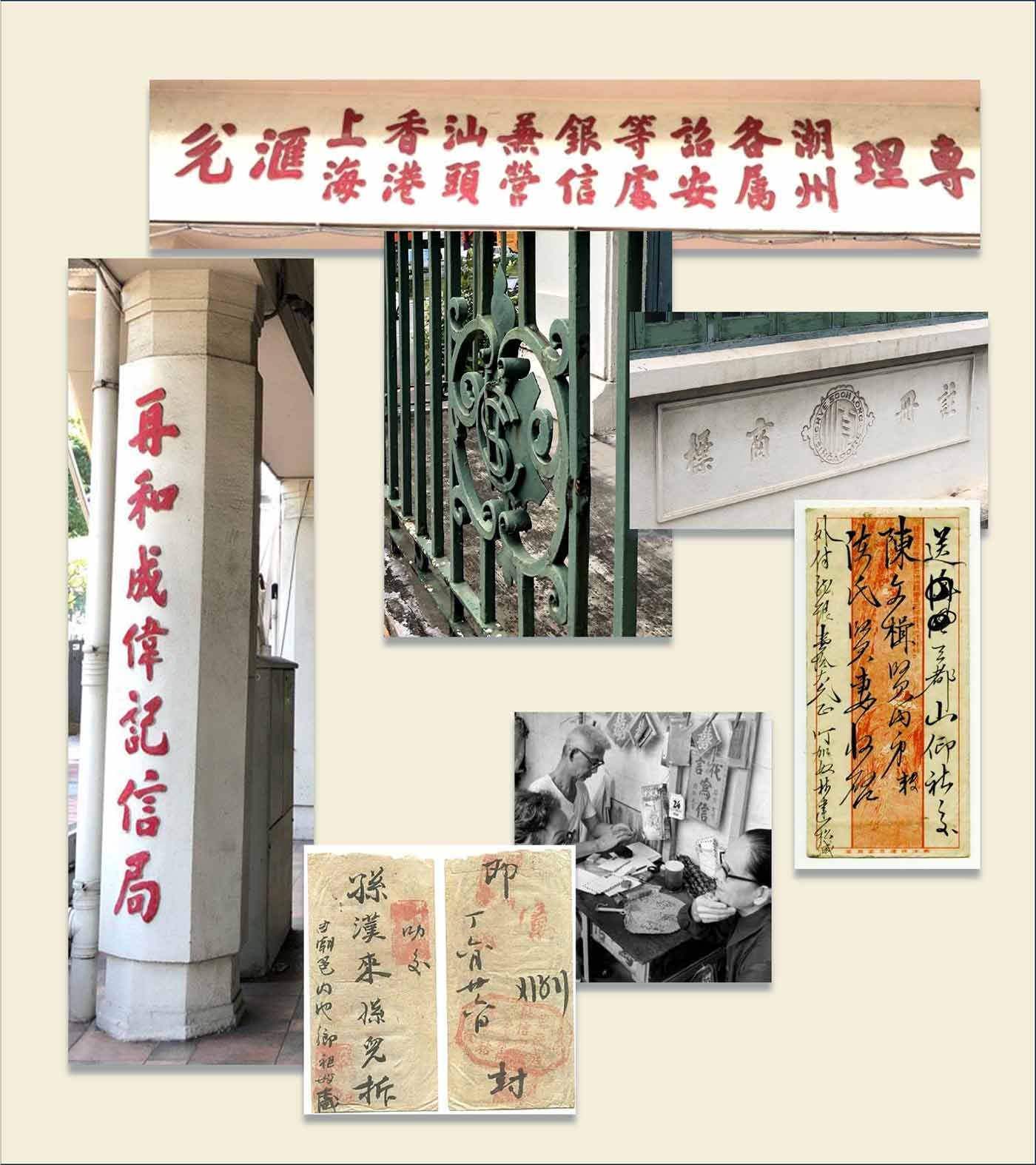

The shophouses were built as the headquarters of the Chye Hua Seng Wee Kee remittance company. Through detailed research into the National Archives of Singapore, WOHA Architects (WOHA) uncovered the history of the heritage shophouses and their context, which informed a rich design approach.

Perhaps the most fascinating of the discoveries was a collection of poetically composed remittance letters that had accompanied the financial transactions – a moving record of the lived experiences of Chinese migrant workers. By incorporating segments of these letters into the design, WOHA builds an emotional connection to the past for today’s travellers.

Having only been in the hands of one family, the shophouses were almost fully intact when purchased by the developer. This is unusual for heritage buildings in Singapore, and the surviving features presented unique opportunities for the new design.

At the same time, in keeping with WOHA’s core values, opportunities for sustainability were thoroughly investigated. As a result, 21 Carpenter combines passive strategies, such as sun shading, natural ventilation, greenery, and daylighting, with active components such as photovoltaic panels and hybrid cooling to lower the building’s energy consumption and enhance the guest’s experience of the tropics.

The ambitious approach extended to efforts to maximise the building’s utility for the community. The creation of a ground-floor hospitality venue, which serves its neighbourhood as well as hotel guests, contributes to the ongoing resilience of the building. The shophouses continue their life as a living part of the district.

About the Designer

WOHA Architects was founded by Ar. Wong Mun Summ and Ar. Richard Hassell in 1994. The Singapore-based practice is focused on researching and innovating integrated architectural and urban solutions to tackle the problems of the 21st century such as climate change, population growth, and rapidly increasing urbanisation.

WOHA’s projects are living systems that connect to the city as a whole. With every project, the practice aims to create a matrix of interconnected human-scaled environments that foster community, enable stewardship of nature, generate biocentric beauty, activate ecosystem services, and build resilience. WOHA applies their systems thinking approach to architecture and urbanism in their building design as well as their regenerative masterplans.

The practice has received a number of international awards such as the Aga Khan Award, RIBA Lubetkin Prize, International High-Rise Award, CTBUH Urban Habitat and Best Mixed-Use Building, CTBUH Best Tall Building Worldwide, and World Architecture Festival World Building of the Year. WOHA has also received numerous P*DA accolades since 2006. The firm currently has projects under construction in Singapore, Australia, and other countries in South Asia.

Hassell graduated from the University of Western Australia (UWA) in 1989 and was awarded Master of Architecture from The Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) University in 2002. He has lectured at many universities, had served as an Adjunct Professor at UWA, and was appointed the Seidler Chair in the Practice of Architecture at the University of New South Wales in Sydney.

Hassell has always been drawn to the intersection of architecture, art, history, and science, four disciplines that offer different but complementary ways of understanding the world. Science explains how the natural world works and opens pathways to sustainability, technology, and deeper engagement with nature. History tells the story of how we arrived here. Art captures the cultural currents of our time. When brought together through architecture, these perspectives allow us to express who we are, where we come from, and how we see the world.

This holistic view shapes Hassell’s approach to design, where form follows systems: social, economic, ecological, cultural, and technological.

DESIGN ARCHITECT FIRM

WOHA Architects Pte Ltd

Richard Hassell, Phua Hong Wei, Fu Yingzi, Rainbow Lee, Mappaudang Ridwan Saleh, Christina Ong, Chong Siew Way

MECHANICAL AND ELECTRICAL ENGINEER

Bescon Consulting Engineers Pte

CIVIL AND STRUCTURAL ENGINEER

Ramboll Singapore Pte Ltd

QUANTITY SURVEYOR

WT Partnership (S) Pte Ltd

PROJECT MANAGER

Jones Lang Lasalle Property Consultants Pte Ltd

CLIENT

8M Real Estate Pte Ltd

LIGHTING CONSULTANT

Lighting Planners Associates (S) Pte Ltd

SIGNAGE CONSULTANT

Radical Design Partnership Pte Ltd

ACOUSTIC CONSULTANT

Alpha Acoustics Engineering Pte Ltd

CONSERVATION CONSULTANT

Studio Lapis

ARTWORK CONSULTANT

The Artling

IT CONSULTANT

RED Technologies (S) Pte Ltd

MAIN CONTRACTOR

Sunray Woodcraft Construction Pte Ltd

DESIGN ARCHITECT FIRM

WOHA Architects Pte Ltd

Richard Hassell, Phua Hong Wei, Fu Yingzi, Rainbow Lee, Mappaudang Ridwan Saleh, Christina Ong, Chong Siew Way

MECHANICAL AND ELECTRICAL ENGINEER

Bescon Consulting Engineers Pte

CIVIL AND STRUCTURAL ENGINEER

Ramboll Singapore Pte Ltd

QUANTITY SURVEYOR

WT Partnership (S) Pte Ltd

PROJECT MANAGER

Jones Lang Lasalle Property Consultants Pte Ltd

CLIENT

8M Real Estate Pte Ltd

LIGHTING CONSULTANT

Lighting Planners Associates (S) Pte Ltd

SIGNAGE CONSULTANT

Radical Design Partnership Pte Ltd

ACOUSTIC CONSULTANT

Alpha Acoustics Engineering Pte Ltd

CONSERVATION CONSULTANT

Studio Lapis

ARTWORK CONSULTANT

The Artling

IT CONSULTANT

RED Technologies (S) Pte Ltd

MAIN CONTRACTOR

Sunray Woodcraft Construction Pte Ltd

1ILLUMINATING THE PAST

The facade lighting highlights the different architectural languages of the conserved and new blocks. It draws attention to the ornate details of the shophouses, whereas the new extension is softly washed by light in a way that emphasises its planar surfaces.

2OLD MEETS NEW

The articulated facade of the conserved four-storey shophouses contrasts with the dematerialised, weightless character of the five-storey contemporary extension. When the building is viewed from Carpenter Street, the impression that the new block floats above the old one is striking.

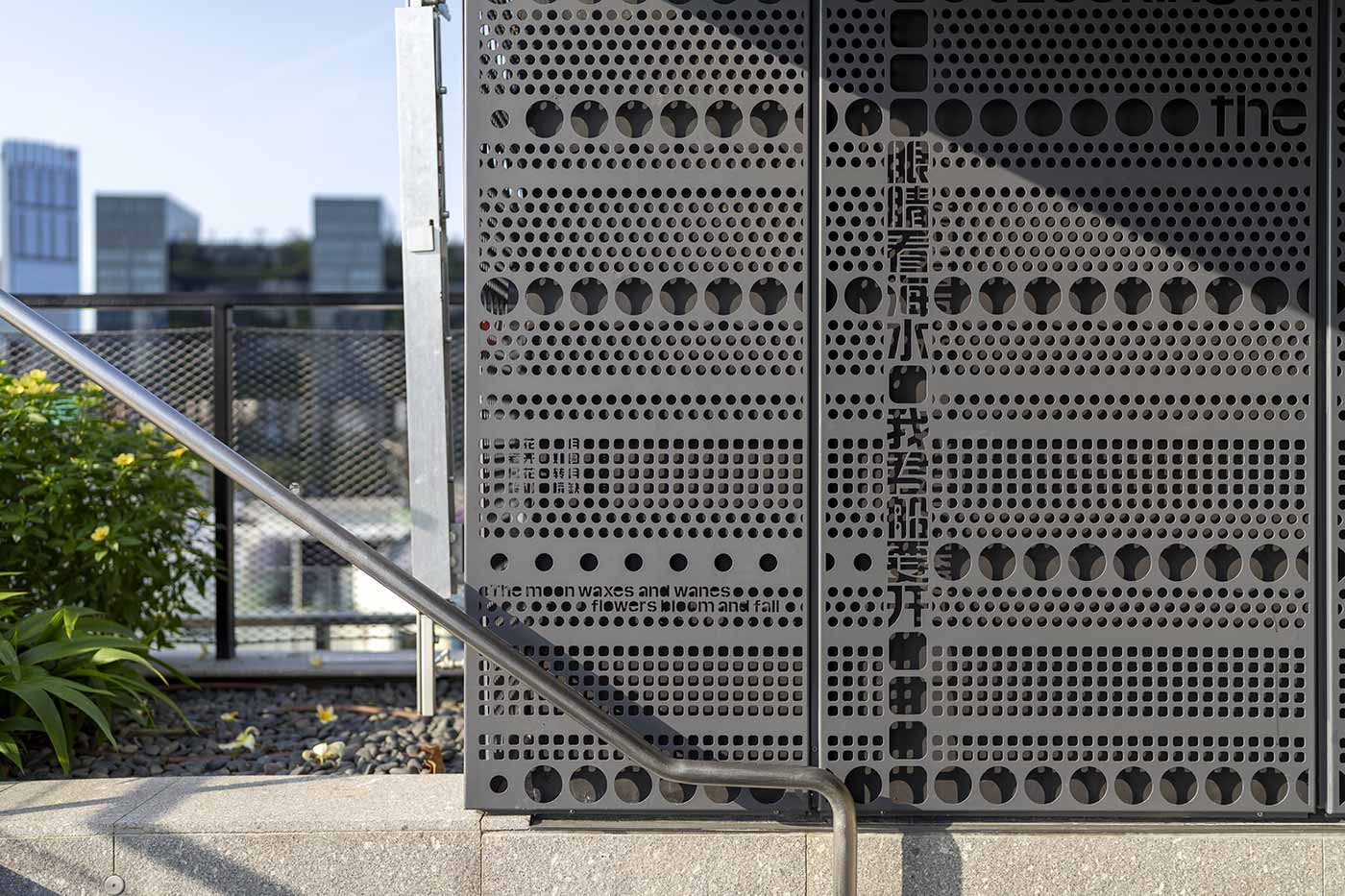

3POETIC FRAGMENTS

The aluminium facade is an artwork that translates text into patterns of horizontal and vertical perforations. These were inspired by the inscriptions on historic buildings in Chinatown, as well as the letters sent by the remittance house that originally occupied the shophouses.

4LINKS TO HISTORY

WOHA’s research revealed the historic prevalence of text in the built environment of Chinatown, as well as the practice of engaging classically trained writers in the neighbourhood to compose poetic letters for family members.

5GARDEN NETWORK

The greenery at 21 Carpenter contributes to pockets of rooftop vegetation in densely built-up Chinatown. Ar. Richard Hassell has observed that the neighbourhood’s network of elevated gardens attracts birds, which move from one to another as part of a daily routine.

6CURRENCY AND SENTIMENT

The remittance letters accompanying the wages sent home by labourers included poems that spoke of a longing for home and family.

7FRAGMENTS OF TEXT

A conceptual model created by WOHA conveys the intent for 21 Carpenter to be a vessel for textual communication.

8COMFORTABLY COOL

All guest rooms use an innovative hybrid cooling system, which combines air conditioning with low-speed fans to create comfort and reduce energy consumption. Bedheads feature calligraphic fragments, continuing the textual theme.

9SPATIAL PRESERVATION

In the heritage block, the 5.7 m grid of the shophouses was preserved internally. This has enabled every room to benefit from its own window, or multiple windows in the case of suites.

10ART OF LOUNGING

The hotel features artworks by Singaporean artists throughout, including in the rooftop pool lounge, which doubles as an event space.

11BOTANICAL HERITAGE

The garden terrace opens up to the adjacent laneway. The planting scheme includes gambir, pepper, and nutmeg. These link the terrace to the building’s original visitors, many of whom were labourers who grew, packed, and shipped these commodities.

12DINING ACROSS ERAS

Kee’s Neo-Bistro and Bar (Kee’s) has a fully glazed shopfront that reveals the activity within. Original Chengal wood beams were upcycled into furniture and interior features throughout the hotel, including several touchpoints within Kee’s.

13TIME’S HORIZON

A rooftop infinity pool offers views of Singapore’s central business district and beyond. The view is a reminder of the city state’s impressive growth into a global financial centre.

14BRIGHT ASPECT

The lobby is a skylit double-height social space that alludes to traditional shophouse courtyard spaces. The interior design features a contemporary interpretation of 1930s Chinese art deco.

Insights from the Recipient

RICHARD HASSELL (RH): There are all kinds of authenticity and we explored a few different types. One type is technical heritage authenticity, which refers to the original form of the building and the evidence of how it’s been used over time. We were lucky that the old building had been covered with paint quite early on in its life, so the original Shanghai plaster was in pretty good condition underneath. We worked with Studio Lapis, our conservation consultant, to gently remove the paint and we discovered three different tones of Shanghai plaster. Even the windows are mostly original because the overhangs sheltered the timber frames from the rain.

The main corner of the building had stayed with the old family, but they’d rented out other parts of it, so there’d been various signs attached to it at different points. We were keen to leave these traces of past tenants. We left the holes in the facade where they’d hammered in wooden pegs to fix signs. We wanted to show the marks of age and not make the building look brand new again.

As an architect, I also like spatial authenticity. This is another type of authenticity we explored. I’m often disappointed in shophouse reuse projects where the interior space gets all chopped up and made into small rooms. You don’t get a sense of the tall and deep shophouse form. We decided that the rooms at 21 Carpenter would always follow the party wall locations, so the windows would fit nicely in each space. There’s a geometric and architectural authenticity to this.

When you do a shophouse extension with a larger block at the back, you also tend to lose the understanding of the shophouse courtyard. So, we designed the lobby as a kind of courtyard that’s glazed and internal. You can look up and see the back facade of the front block, the eaves, and light coming over the roof.

Finally, this building was an opportunity to explore a kind of authenticity of connection with people from the past. We wanted to create an emotional connection between the hotel guests and the original users of the building, the migrant workers who were sending money and letters back home. This idea of a connection across 90 years to other travellers to Singapore who were missing home led to the concept for the facade artwork.

We selected phrases from the remittance letters to create this emotional resonance. These weren’t the raw words of the workers themselves, as we found out that they engaged classically trained letter writers in Chinatown. I love the idea of the workers’ sentiments being framed through the words of the great classic poets of Chinese literature. Even now, you can feel the emotions carried across the decades.

RH: When I was looking at old pictures of Chinatown, I realised that Singapore, like Hong Kong in those days, had signage everywhere. Chinatown was a textual environment. The idea of text was interesting for 21 Carpenter because we wanted something for the new block that is obviously contemporary, but still has materiality, denseness, and texture that’s harmonious with the Shanghai plaster and mouldings of the old building.

The perforated facade came from the idea of wrapping the new block in text. We were also worried about it overwhelming the old building because it’s a lot taller. We wanted to make it seem weightless, very thin and folded like origami, so it appears to float. That would also allow the old building to have gravitas.

RH: It was a nice building to begin with, so that made it very easy. It had such interesting features, like the windows, which informed our idea to keep the room bays. They’re large, almost wall-sized windows, but they’re framed with wood, which is unusual. In the 1930s, there was a transition underway to steel-framed windows, but here they were still made of wood. They form a wall of glass composed of typical smaller windows. The buildings of the 1940s became quite different because a steel frame could make a whole window wall.

Every room has great light, air, and views, which is unusual for a shophouse project. Often you get, say, four great rooms facing the street, and then 20 awful rooms, some of which either have no windows, or simply overlook the air conditioners at the rear. I think our rooms are all good. We were driven by an urge to conserve more than we had to, and to celebrate the original experience of the building, rather than just treating it as a fancy facade stuck in front of an ordinary hotel.

RH: Solving the problems of the old rooms set the tone for the new rooms. Our idea was that whether you stayed in the old or new block, you had a consistent experience. We designed contemporary interpretations of 1930s Chinese furniture, referencing modern and art deco teak pieces. We reused all the wooden floors in the old building and kept them as we found them. They had nail holes and broken edges, which we filled with epoxy. We then gave the new block a recycled oak floor.

The windows in the new block are proportioned similarly to those in the old block. In all the bathrooms, we used frosted fluted glass, which has a 1930s feel. The corridor carpet and bedheads also feature abstracted calligraphy.

We recycled the timber joists found throughout the old building. They’re used for the door handle and window frames in the restaurant, the reception desk, the lobby floor, and the handrails at the ramps in the five-foot way. They’re such beautiful pieces of wood: 100-year-old Chengal in perfect condition.

RH: On paper, the building had a concrete frame, so as we designed it, we anticipated being able to knock down some internal walls. Then, once we were on site, the engineer said, “Hang on a minute. This is a very strange structure.” Even though they had investigated a typical column and a beam and they looked in decent condition individually, it turned out that the concrete structure as a whole was not rigidly tied together as you would expect in a modern concrete building.

Again, this was because of that transition in technology from brick and timber to concrete. The 1930s engineers were obviously not so comfortable with concrete, so they designed it like wood.

We had to stiffen the structure by wrapping the old concrete skeleton in steel. Every beam was cradled and picked up on a steel beam, which connected a new steel column that extended all the way down to new piles and foundations. These had to straddle the old piles without adding more load. Our columns tripled in size and we lost a bit of headroom. We then carefully set the steel structure into the thickness of the perimeter brick wall so that the external facade retained its original thickness.

These were all technical challenges, but they were quite significant, because in a hotel you’re always working at the scale of small objects and finding ways to tuck things in wherever possible.

RH: The old building was designed for cross-ventilation and ceiling fans, not air conditioning. Nowadays, tourists who come to Singapore say, “It’s so cold inside the buildings. I got sick on the second day from going back and forth between the hot, humid air and the cold interiors.” We wanted to try out a hybrid cooling solution that we had previously developed with Transsolar, a climate consultant working in the area of thermal comfort, for the BRAC University project in Bangladesh.

We explained to our client that if they set the air conditioning to 26 ºC and used a fan, the fan would make it feel like 24 ºC. It would save energy and reduce how sick people feel because there’s less temperature variation. The client agreed to do it. We’re now using the same technique in another hotel we’re designing. I think opinions around air conditioning have changed, which is a great advancement.

RH: We’ve done a couple of projects with greenery on North Canal Road, as well as PARKROYAL COLLECTION Pickering and our rooftop at the WOHA studio on Hongkong Street. There are quite a few shophouses and other buildings around us that have added greenery. It’s quite interesting that even Chinatown, which has a hundred percent site coverage, is becoming green. Biodiversity increases significantly just having these small pockets of plants in the area.

Sunbirds visit our rooftop garden at WOHA and make nests. We see a variety of birds flying from rooftop to rooftop. To them, it’s just their neighbourhood. They have a daily routine: Check out the flowers on our rooftop at 10am, and have a little bath at 21 Carpenter when the sprinklers go off in the morning. It’s very nice when wild creatures move in based on what you’ve done.

RH: The developer, 8M Real Estate, really wanted the restaurant to be a place where everyone in the neighbourhood can work, bring their clients, and get to meet each other. There was a great vision of it being the neighbourhood bistro or coffee shop, and it’s really worked. It has started a community.

From a design point of view, we thought it was important to expose this activity to the street so people know it’s there. We brought the open kitchen out to the first shophouse bay, so you can see the chef preparing things with care and skill. We put the bar in a pivotal position at the corner. We also made lanterns and lamps that we placed around the restaurant to draw people in. All these things are design aspects of a central idea that this is a place with low barriers to entry. It’s a place for the neighbourhood to come together.

RH: No, I don’t think there is. It is one way of making people really connect to a building. A lot of people feel that architecture is big business. It seems very technical and mysterious to people outside the profession. But because it’s a capsule of human life, I think it’s filled with emotion. It endures, so it immediately becomes about the past, past emotions, and stories of where people come from.

Even when we talk about sustainability, I think about it in terms of environmental grief. If the building appears to be, in some small way, reversing a trend of loss and destruction, that makes people feel quite emotional about it as well.

RH: It comes back to the question of authenticity. 21 Carpenter is about a kind of heritage experience where it doesn’t feel like you’re playing make-believe, pretending you’re back in the past. It’s not a stuffy heritage experience because it never was that kind of place. It was a place of business, a node in a financial network across the world. Our take on it was that it should feel like it’s a useful space for the modern-day traveller.

When you stand on the roof terrace and look out to the Singapore River, you can see the Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation (OCBC) and United Overseas Bank (UOB) towers. This remittance house, through a series of mergers and acquisitions, ended up being part of OCBC. So, this little building is part of the story of how Singapore became a financial hub. From small beginnings, big things can grow.

The building’s narrative of connecting you to migrant workers makes you think, “Here I am in 2025, another person trying to build my life through travelling and business, and I’m just part of a long story of people making their way in the world through this unique little corner of Asia.”

Citation

Jury Citation

Nominator Citation

Sun Mi Moon

Executive Director, Asset & Development Management

8M Real Estate Pte Ltd

21 Carpenter is a well-crafted boutique hotel that interweaves and juxtaposes the contemporary rear block with four conserved shophouses in a cohesive way that honours its history. The elegant articulation of its five-storey extension floats above the heritage structure, contrasting with the charming shophouses beneath. Its chamfered corner creates a terrace that brings air and daylight into the existing building.

As one moves through the conserved shophouse, the carefully positioned skylights frame glimpses of the modern extension above, creating a subtle interplay between the old and new. In the new extension, heritage elements of the old building are revealed and reframed, unveiling new viewpoints and understanding of the building’s past as a remittance house. Throughout the building, there is a strong sense of storytelling that reflects the building’s heritage. One can find glimpses of history such as the Chinese labourers’ inscriptions from their remittance letters on the perforation of the facade screens.

The jury commends the team’s design finesse, evident at every level of the project – from its bold massing and sculptural form to the refined detailing of interiors and material articulation.

It is with great pride that I write to endorse 21 Carpenter for the prestigious President*s Design Award 2025. As a real estate developer invested in the conservation and celebration of Singapore’s architecture heritage, I believe in the transformative impact that thoughtful conservation projects can have for our community and neighbourhood. 21 Carpenter stands as a remarkable example of this.

WOHA’s design for 21 Carpenter serves as a showcase of how a conservation project can successfully harmonise the past with its present and future. It strives to preserve the essence of Singapore’s heritage, as well as the physical built elements of a shophouse, while embracing the new. Physically and figuratively, its history and conserved wing sit as the foundation that inspired and lifted the design of the new wing. This idea is present at smaller scales as well. Walking through 21 Carpenter, you can see the sensitive restoration work that reveals the beautiful ageing of the original Shanghai plaster. And just above are the floating facade panels to help manage solar heat gain. There’s an almost magical moment where you cross over from the conserved block to the new block, and there isn’t a clear threshold or a signal on when and how it happens.

21 Carpenter is also a showcase of Singapore design excellence. WOHA’s contribution to Singapore’s urban landscape and its design industry is well known. Richard Hassell and his team’s passion and dedication for excellence made my experience working on this project particularly enriching. This collaboration between our team, as the owner-developer and Richard’s team, was a true partnership. It was filled with active dialogue and mutual respect. Throughout the five years of design and the difficult construction phase, we were able to have open discussions. Looking at how 21 Carpenter turned out, I am ever more appreciative of the design team’s guidance through many hard decisions.

Seeing a quiet and sleepy corner of Carpenter Street transform back into what must have been a buzzing and dynamic street has been rewarding. We are confident of its future success. 21 Carpenter deserves the President*s Design Award for its achievement of celebrating Singapore’s architecture heritage through design excellence. It will set a new standard for conservation projects globally.