DESIGN OF THE YEAR 2020

GoodLife! Makan

Designer

DP Architects Pte Ltd

CONTACT

[email protected]

Food indeed brings people closer together at GoodLife! Makan. At this Senior Activity Centre in the Marine Terrace estate, a group of elderly residents comes by daily to voluntarily prepare meals for one another.

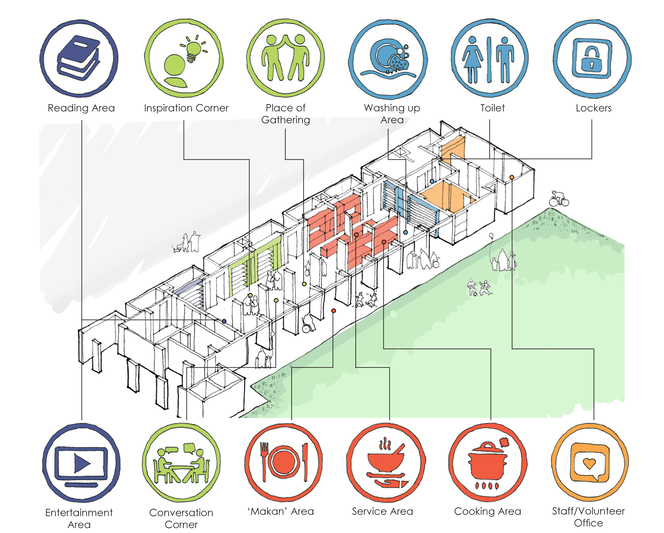

It deviates from the traditional care model where meal deliveries and other such services are provided to seniors at their doorstep. To draw out stay-alone seniors from their apartments, the open ground-level void deck of a public housing rental block was transformed into a community kitchen and living room. The kitchen sits at the heart of the 360 sq m space to allow chance encounters as seniors prepare ingredients, cook meals and wash dishes. These activities happen in different zones which are segmented by bright colours and icons. These visual markers help the group, who are of different linguistic and ethnic backgrounds, to better understand one another. Surrounding the centre are full-height glass doors which are kept open to allow for cross ventilation and, more importantly, welcome the community in.

This simple but bold departure from the typical enclosed Senior Activity Centre has gone beyond creating a vibrant hub for ageing-in-place. It has transformed a group of seniors from recipients of charity to stewards of their own community.

About the Designer

Driven by DP Architect’s core philosophy of purposefully synergising people and place, Ar. Seah Chee Huang and his team focus on the design and planning of various multi-stakeholder and integrated community, sports, civic, cultural and commercial lifestyle complexes in Singapore.

The design team adopts a human-centric design approach that responds to evolving socio-economic dynamics while pursuing social and environmental sustainable innovations. With a deep empathy for emotional and psychological needs, the team synthesises distinct spatial, programmatic and material interventions, with participatory design processes, to develop unique and purposeful design outcomes that allow the re-imagination of the environment and empower participation.

Chee Huang is the Chief Executive Officer of DP Architects and its group of companies. He leads the design and planning of various local and overseas project types, especially in complex mixed-use as well as major integrated community and sports developments. A firm believer in a people-centric and participatory design process, he is actively involved in the engagement of stakeholders, grassroots and residents to achieve strategic and synergistic design outcomes.

DESIGNER

DP Architects Pte Ltd

CLIENT

Montfort Care

MAIN CONTRACTOR

Stancel Construction Pte Ltd

MECHANICAL & ELECTRICAL ENGINEER

Bescon Consulting Engineers Pte

DESIGNER

DP Architects Pte Ltd

CLIENT

Montfort Care

MAIN CONTRACTOR

Stancel Construction Pte Ltd

MECHANICAL & ELECTRICAL ENGINEER

Bescon Consulting Engineers Pte

1EATING TOGETHER

This Senior Activity Centre uses a community kitchen and living room concept to bring together stay-alone senior residents in Marine Terrace estate.

(Photo by DP Architects Pte Ltd)2EATING TOGETHER

This Senior Activity Centre uses a community kitchen and living room concept to bring together stay-alone senior residents in Marine Terrace estate.

(Photo by DP Architects Pte Ltd)3EVERYDAY INTERACTIONS

The centre is organised around the different cooking rituals, from preparing ingredients to cooking, dining and washing up. This creates opportunities for its users to interact with one another.

(Photo by DP Architects Pte Ltd)4OPEN DOOR POLICY

Full-height doors, which are kept fully open during the facility’s operation, are a key design feature. It creates an inviting environment, unlike similar centres elsewhere which are typically enclosed.

(Photo by DP Architects Pte Ltd)5REFRAMING ROLES

By allowing seniors to voluntarily cook for and with one another, the centre reinstates their self-worth and helps them overcome social isolation.

(Photo by DP Architects Pte Ltd)6ACTIVE AGEING

Unlike traditional aged living facilities which usually have muted colour schemes, the centre adopts a palette of vibrant colours. Various icons were also designed to help seniors of different language groups communicate easily with one another.

(Photo by DP Architects Pte Ltd)7ACTIVE AGEING

Unlike traditional aged living facilities which usually have muted colour schemes, the centre adopts a palette of vibrant colours. Various icons were also designed to help seniors of different language groups communicate easily with one another.

(Photo by DP Architects Pte Ltd)8ACTIVE AGEING

Unlike traditional aged living facilities which usually have muted colour schemes, the centre adopts a palette of vibrant colours. Various icons were also designed to help seniors of different language groups communicate easily with one another.

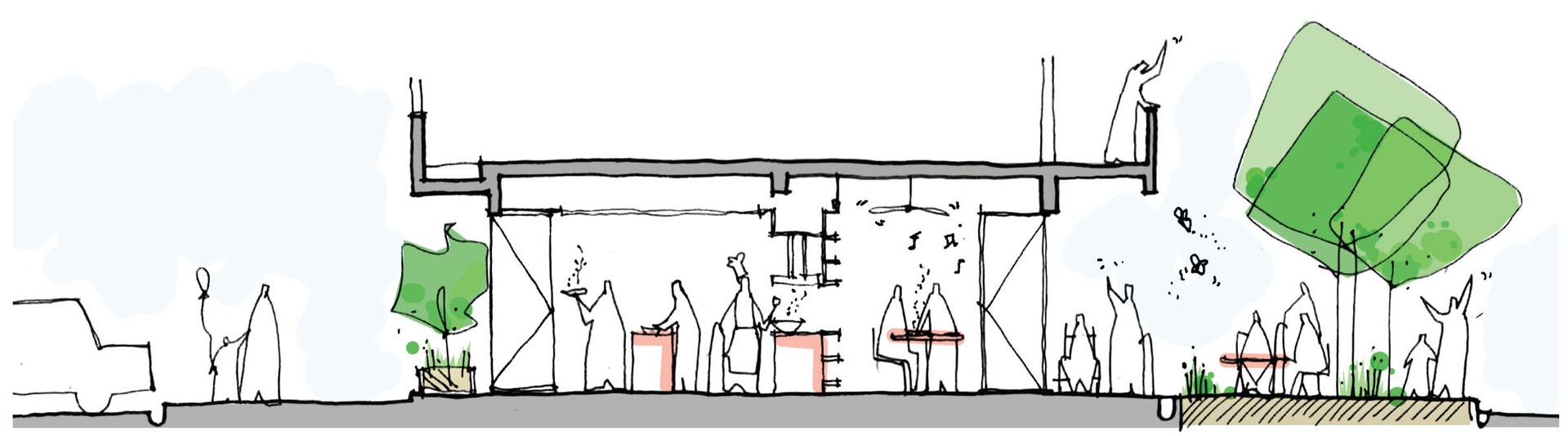

(Photo by DP Architects Pte Ltd)9VOID NO MORE

The centre’s open design retains the original character of the void deck, a common feature in public housing estates in Singapore. It offers a prototype for transforming similar spaces across the island into ageing-in-place facilities.

(Sketch by DP Architects Pte Ltd)10VOID NO MORE

The centre’s open design retains the original character of the void deck, a common feature in public housing estates in Singapore. It offers a prototype for transforming similar spaces across the island into ageing-in-place facilities.

(Photo by DP Architects Pte Ltd)11VOID NO MORE

The centre’s open design retains the original character of the void deck, a common feature in public housing estates in Singapore. It offers a prototype for transforming similar spaces across the island into ageing-in-place facilities.

(Photo by DP Architects Pte Ltd)12VOID NO MORE

The centre’s open design retains the original character of the void deck, a common feature in public housing estates in Singapore. It offers a prototype for transforming similar spaces across the island into ageing-in-place facilities.

(Photo by DP Architects Pte Ltd)13(L-R) Melcas Lim and Seah Chee Huang

(Photo by Ivan Loh, pigscanfly photography)Insights from the Recipient

Seah Chee Huang (SCH): Singapore is facing a “silver tsunami” – it is projected that one in four Singaporeans will be above 65 years old by 2030. Within this group is a vulnerable community of stay-alone seniors who are isolated from society and could face depression or even death in their homes. There were 47,000 of them in 2016 and the numbers are expected to almost double by 2030. This was what we learnt when Montfort Care, a non-governmental organisation, approached us to design a Senior Activity Centre. Traditionally, the organisation would go door-to-door to provide services for seniors, but therein lies a problem. While it addressed the essential needs of seniors, this also made it unnecessary for them to step out of their homes. What was powerful about this project was that it questioned such a model of social support. Through programming and design, it allowed us to relook at how to better address both the existential and emotional needs of these seniors purposefully.

SCH: At the core of the centre, we introduced a “community kitchen” surrounded by an open and flexible “living room” that could accommodate up to 60 people. The other facilities such as the office, storage spaces and basic amenities were placed at the ends of the centre. The kitchen was organised to complement the different rituals of cooking – from food preparation to cooking, dining and washing up – which we hoped can create many opportunities for interactions. The centre was zoned into distinctive areas using colours, icons and even food ingredients as a common language for seniors of different linguistic and ethnic backgrounds to communicate with one another. A palette of vibrant colours was also used to convey liveliness as the client wanted to debunk the generic association of aged living with a muted and sterile setting.

While the design of the space breaks down some inherent emotional and social barriers faced by the seniors, it also shifts the perception of these stay-alone seniors from recipients of charity — someone that you give food to — to active stewards of the community. In the process of helping themselves, these seniors are also providing for others through food. It reinstates their sense of self-worth. One of my favourite stories from the project is an anecdote from a senior, Mr Looi. When he was first approached and asked how the centre and staff could help him, Mr Looi rejected the offer. But after the idea of GoodLife! Makan was conceived, he warmed up to the Montfort Care team and agreed to help out at the community kitchen. Design has the capacity to reframe the way the community sees these seniors and the way they see themselves.

SCH: Another key question we had and wanted to challenge was the traditional construct of a typical senior activity centre and how it could be reimagined. From our studies, most of such centres located in the public housing void decks are either gated or treated like “fish tanks” as they are fully glazed up. These spaces are often clearly defined to offer security for the seniors. But in the case of Goodlife! Makan, we were designing for stay-alone seniors. The idea of a self-contained centre would not have helped stay-alone seniors overcome social isolation nor destigmatise the public’s perception of them.

Originally, we conceived the centre as an entirely open space. But the client raised several practical concerns about thermal comfort or situations of haze. To address these issues, we employed a key architectural component that is one of the centre’s key features – the door. The entire facade of the centre has a series of full-height doors to create a welcoming space and to suggest that one can enter the centre from all around. By keeping the doors fully open during operation, we blur the boundary between the centre, corridor and larger estate. It also maintains the original character of the void deck and allows for cross-ventilation which minimises the reliance on air-conditioning.

In fact, when the centre first opened, many curious residents walked in thinking it was a café. It became an opportunity for the centre’s social workers to share with them about its programme and even recruit new volunteers!

SCH: Since its opening, Montfort Care staff have received many positive comments. There were also many visits from ministries, agencies and foreign delegates. They were interested to find out more about its design and programme. The seniors who were engaged were happy with the centre.

After the project was completed, Montfort Care staff shared light-heartedly that our project was giving them new issues as they had to manage seniors bickering over what to cook and their different roles. I was honestly quite excited when I heard this as it validates how we have fostered social interaction among them through design. By communicating with one another about what to achieve together, the seniors have gained a newfound sense of purpose and ownership at the centre. Such negotiations are essential aspects of everyday life and through the exchanges, we have successfully reintegrated these socially isolated seniors back to the community.

Over these past years, the centre has been very well used and we recently worked with Montfort Care’s team to update it. The design principles remain the same, but we have added new equipment, surfaces, more greenery and a café. The updated centre also offers a dedicated space for day-nursing care run by Montfort Care in partnership with Singapore General Hospital. It is interesting to see an ecosystem of community-based care emerging through the centre. We are working with Montfort Care to look at how its entire network of centres at the Marine Terrace estate, which caters to different needs such as an elderly gym and a family welfare centre, can start to synergise better with one another through design. As void decks are an integral part of Singapore’s public housing landscape, they offer an abundance of opportunities for more of such meaningful centres. They can be designed based on the needs of different communities and, more importantly, build greater cohesion and care for one another.

SCH: Size matters but small can be beautiful too. The centre may be modest in scale, but ithas generated a lot of discussion and even discourse in the domain of ageing-in-place and community-based care infrastructure. The current mode of eldercare often involves physically moving a person to an institution to be healed, so, physically, they are being looked after but there is a psychological impact that may not be sufficiently addressed. Studies show that familiarity of a place in terms of sights, sounds and people is extremely important in anchoring seniors and giving them a sense of security.

GoodLife! Makan shows that smaller scale, ground-up community support networks can complement robust top-down social support systems that are currently in place in Singapore. In this case, it happens within an estate where we get seniors to come together to help each other. What we need are institutions and ground-up initiatives to work synergistically to create a holistic care ecosystem that is truly inclusive for our seniors.

Citation

Jury Citation

Nominator Citation

Samuel Ng Beng Teck

Chief Executive Officer

Montfort Care

GoodLife! Makan has pioneered a successful prototype to purposefully reintegrate stay-alone elderly back into the community and enliven the idea of ageing-in-place. The project is a delightful remake of the Senior Activity Centre and the conventional meal delivery service for seniors.

Located below a public housing block in the ageing estate of Marine Terrace, the facility invites seniors to become volunteers for one another. It uses the common language of food to bring them together and co-create programmes that serve one another’s needs. Through their active engagement – from food preparation to cooking, serving and washing up – the seniors feel empowered and gain a sense of ownership in the centre.

The facility is also designed as a welcoming space for all. Its porous compound allows for cross ventilation and blurs its boundaries with the void deck corridor. The interior’s vibrant colours add a sense of energy, while the displays of familiar heritage foods stimulate the minds of persons with dementia.

The Jury is impressed by how this impactful and inspiring community project turns Senior Activity Centres on their heads. It has the potential to scale up and help elderly across Singapore to shape their own “GoodLife!” community spaces.